By Richard Farmer

I have recently been doing some research into the sports and social clubs established at British film studios, seeking to understand how the various sporting events, leisure activities and outings they organised functioned as elements of workplace culture. I have also been exploring sporting competitions organised between different studios, and between studios and firms operating in different parts of the British film industry.

During this research, I came across references to on-set cricket matches played at Shepperton during the production of Private’s Progress in the summer of 1955. These matches took place during the working day, so were different from most of the sporting events that I’ve been looking at which were scheduled for weekends or during workers’ leisure time. If anything, the Private’s Progress cricket matches are aligned with the kinds of activities discussed by Morgan in a previous STUDIOTEC blog, in that they provided a means of killing time during the tedious longueurs of film production. Using these games as a starting point, I decided to look into cricket in British film studios.

Private’s Progress was directed by John Boulting, and produced by his twin brother Roy, both of whom, in the latter’s words, ‘feel passionately about cricket’ (Furlong 1959: 634), and were known to use slightly tortured cricket metaphors to hit out at criticism of British films (see, for example, Boulting 1959: 6). Although the sport features in several of their films, so sincere was the brothers’ love for cricket that when asked in 1959 if they had ever thought about producing a cinematic satire on the game, as they did about the army in Private’s Progress, academia in Lucky Jim (1957) and industrial relations in I’m All Right Jack (1959), Roy replied: ‘Good heavens, no. One can’t be funny about cricket. It’s a sacred subject’ (Furlong 1959: 634).

There were times, however, when cricket injected a degree of humour into the making of Private’s Progress. When Alan Hackney, from whose novel the film was adapted, visited Shepperton, he found the Boultings seemingly more interested in the fourth Test then being played against South Africa in Leeds than they were in the production of their film. As England tried, and ultimately failed, to hold on for a draw on the final day, the brothers received regular updates about the state of play and regularly gave voice to their nervous preoccupation: John – ‘I can’t stand it’; Roy – ‘I can’t bear it’ (Hackney 1956: 597).

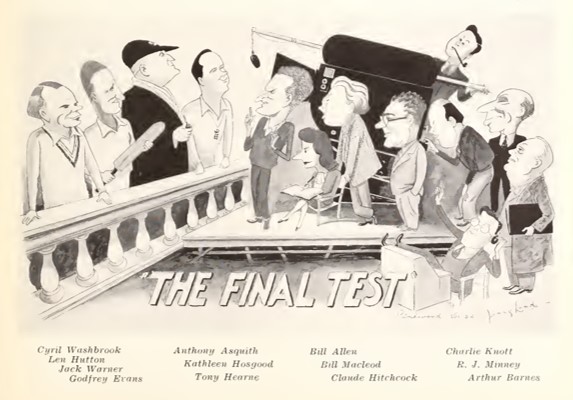

The Boultings were not the only British film industry figures with an interest in cricket. C. Aubrey ‘Round the Corner’ Smith, formerly of Sussex and England, made an acting career in America, and was a founder member of the Hollywood Cricket Club, for whom David Niven, Clive Brook and Boris Karloff all turned out, the latter making the club’s first century. In 1929, Terence Rattigan played for Harrow in the annual match against Eton; 22 years later, as part of the Festival of Britain celebrations, he wrote The Final Test for the BBC, ‘an inevitable outgrowth of [his] early Harrovian division of time between theatre and cricket’ (Rusinko 1983: 3). This television play was remade for cinema at Pinewood in 1952, where parts of the Oval were built in replica after permission to film at the ground was refused. These sets were so detailed that the England cricketers who appeared in the film, including Len Hutton, Denis Compton, Alec Bedser and Jim Laker, were said to have felt very much at home:

These people [said Hutton] had got the atmosphere so complete that I felt I was taking part in a real Test match when I walked out from the pavilion to open the innings with Cyril Washbrook. I forgot everything else, except that I was going to face the bowling and to make the runs (Birmingham Gazette, 21 November 1952: 2).

Trevor Howard was so famously dedicated to the game that he made it clear to prospective employers that there were certain days when he would be unavailable for filming: ‘“Why?” they’d ask. “Test match, amigo,”’ he’d reply (Munn 1990: 50). Indeed, Howard’s contract with the Rank Organisation was said to contain a clause stating that he would not have to work on specific days, so that he could attend international cricket matches (Birmingham Gazette, 18 August 1950: 4). Even when Howard was in the studio during England tests, cricket remained his primary concern, as Edgar Craven found on a visit to Pinewood on 27 June 1950. Howard was supposed to be concentrating on his leading role in The Clouded Yellow (1950), but his heart was evidently at Lord’s, where the West Indies’ batsmen were piling on the runs in the second Test. At various points throughout the day, Howard was found ‘wandering sadly’ around the studio, obsessively muttering the score, his face more despairing, Craven noted, even than those anxiously contemplating the uncertain future of the British film industry (Craven 1950: 3).

Ian Carmichael was another enthusiastic cricketer, which might in part explain why the Boultings cast him in half a dozen of their films. He noted that it was always easy to tell when he was working on a Boulting brothers’ set:

On test match days a blackboard was erected beside the set and it was the prop boys’ responsibility, with the aid of their transistor [radio], to keep the score permanently up to date (Carmichael 1980, p. 315).

Carmichael, who starred in Private’s Progress, was given regular opportunities to play whilst working with the Boultings. Writing for Punch, Hackney noted that there were daily cricket matches at Shepperton during the filming of Private’s Progress and claimed that these often took place during regular brief strikes by members of the studio’s technical crew. Hackney, in a line that wouldn’t sound out of place in one of the Boultings’ comedies, records John as saying that ‘It’ll put days on the shooting, but it enables us to play cricket in the afternoons’ (Hackney 1956: 597).

Yet whereas delays to the production of Private’s Progress allowed cricket to be played, cricket also disrupted the film’s production. Richard Attenborough, who along with co-star Victor Maddern was said by a delighted Roy Boulting to be ‘very keen’ on cricket (Hackney 1956: 597), was knocked unconscious whilst fielding during a stage-versus-politicians charity match at East Grinstead in September 1955:

He was near the boundary and ran forward to take a lofted ball hit by Lieut.-Colonel W. H. Bromley Davenport, Conservative MP for Knutsford. The ball hit him just above the left eye. He collapsed with blood pouring from the injury (Birmingham Post, 12 September 1955: 1).

The match was filmed by the newsreel companies and footage from the event, including a prone Attenborough being carried from the field on a stretcher and Minister of Labour Walter Monckton being bowled by a Rex Harrison grubber, can be viewed here (Pathe) and here (Movietone). Attenborough’s wound required twelve stiches, and he was unable to immediately return to work. This, a studio spokesperson informed the press, necessitated a change in the shooting schedule:

Dickie was to have filmed several scenes [for Private’s Progress] next week, but we shall have to reshuffle the programme to do certain other scenes in which he does not appear until he is better. We are told it will be at least a week (Yorkshire Post, 12 September 1955: 1)

Charity matches were not uncommon, even if injuries of the kind suffered by Attenborough were, and afforded actors and other film practitioners an opportunity to show off their skills for a good cause and/or to generate some useful publicity. In 1950, Howard took a side from Pinewood to play against Cranleigh Junior School in Surrey, in response to a challenge from one of the teachers, who wanted to know how well a team of ‘strange film people [could] do on the cricket field without rehearsals.’ Well enough, it turned out. Howard’s team included producer Betty Box, who had just finished working with him on The Clouded Yellow, and actors Helen Cherry (who was married to Howard), Diana Dors, Jean Simmons, Glynis Johns, Dane Clark and Robert Beatty. These last two, being American and Canadian, respectively, had not played cricket before. Assisted by Simmons’ fourteen with the bat, the schoolboys were bested by three wickets, and some valuable column inches acquired (Rugby Advertiser, 8 August 1950: 3). In July 1953, Terence Rattigan captained a Final Text XI – including both actors and professional cricketers – in a match which raised in the region of £3,000 for the Red Cross, eventually losing by three runs (Minney 1976: 147-7).

The weather for that game was good. The same could not be said of match around which The Final Test revolves, which was meant to have been played on one of Pinewood’s stages, but which was moved onto the studio’s lawn when it was found that competitive cricket could not be convincingly recreated indoors (Middlesex Advertiser and County Gazette, 21 November 1952: 1). Shooting in late November proved challenging. Poor light is the enemy of cricketer and cinematographer alike, and the low, pale winter sun had to be augmented with artificial light from the studio’s lamps in order to give the match an authentic summer glow. Further, the cast’s faces ‘had to be painted over with sun-tan’ before shooting could commence (Minney 1953: 52).

I found no evidence that the Boultings used their studio lights to continue their on-lot matches when the light got bad; rather, when filming outdoors, ‘the moment the shooting was held up for lack of sun the entire unit would move over to play cricket’ (Carmichael 1980, p. 315). In his memoirs, Ian Carmichael remembered that such play was made possible by the brothers’ cricket-conscious forethought:

the … prop boys, in addition to the props required for the day’s shooting, always had to carry in their van a complete set of cricket gear. This, on arrival at our destination, would be set up on some adjacent patch of grass (Carmichael 1980, p. 315).

Having appropriate kit to hand was no doubt useful when filming The Guinea Pig on location at Sherborne School in 1948, where players from the school challenged the crew to a game. Despite the best efforts of Bernard Miles, who ran out three of his teammates, the visitors reached their target with a few minutes to spare, with important contributions coming from photographer Reg Davis, sound recordist Jim Whiting and assistant director J. Hancock (Hassall 2018). Evidently, success on the cricket pitch was as reliant on teamwork as filmmaking.

References

Anon., ‘Film star hurt in cricket mishap’, Birmingham Post, 12 September 1955: 1

Birmingham Gazette, 18 August 1950: 4.

Birmingham Gazette, 21 November 1952: 2.

Birmingham Post, 12 September 1955: 1.

Roy Boulting, ‘Franklyn, you’re so wrong’, Picturegoer, 23 May 1959: 6.

Ian Carmichael, Would the real Ian Carmichael – : an autobiography (London: Futura, 1980).

Edgar Craven, ‘Pinewood weeps over willow’. Yorkshire Evening Post, 1 July 1950: 3

Monica Furlong, ‘The Tatler interviews Roy Boulting’, Tatler, 17 June 1959: 634

Alan Hackney ‘Book into film’, Punch, 16 May 1956: 597-99

Rachel Hassall, ‘The Guinea Pig’, website of the Old Shirburnian Society: https://oldshirburnian.org.uk/the-guinea-pig/ (2018).

R. J. Minney, ‘The Final Test’, Cine-Technician, March-April 1953: 30-1, 52.

R. J. Minney, The Films of Anthony Asquith (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1976).

Michael Munn, Trevor Howard: the man and his films (Chelsea, MI: Scarborough House, 1990).

Middlesex Advertiser and County Gazette, 21 November 1952: 1.

Rugby Advertiser, 8 August 1950: 3.

Susan Rusinko, Terence Rattigan (Boston: Twayne, 1983).

Yorkshire Post, 12 September 1955: 1.

Cricket matches between showbusiness teams has a venerable tradition. Every summer issue of The Era from the 1890s carries scorecards of friendly Sunday afternoon matches between touring theatrical companies, either amongst themselves or against local teams.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Mark; that’s an interesting comparison. C. Aubrey Smith, of course, started his acting career in the theatre before moving to films, and I’m sure there are numerous other examples (although maybe not so many by test cricketers).

LikeLike

Nice information

LikeLike