By Richard Farmer

Ming the panda on set at Marylebone studio. The Sphere, 3 June 1939, p. 384

Here at STUDIOTEC we’re very interested both in the spaces of film production and those that work in them. While this usually means humans, we have not ignored the role that animals have played filmmaking, and dedicated more time than was perhaps strictly necessary to exploring the career of 1930s wonder-dog Scruffy. We also explored the possibility that parts of the Sound City studio at Shepperton might have been turned into a zoo.

Kinematograph Weekly, 12 March 1942

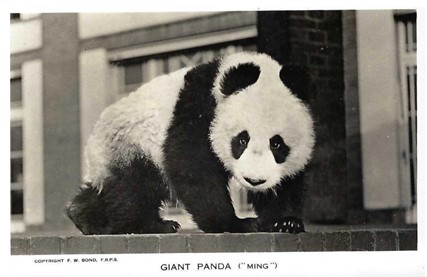

Over the course of our research we have continued to uncover vast amounts of animal-based material, with the headline ‘Worm holds up film production’ being a personal favourite. This blog will focus on one such story, the production of the comedy short Pandamonium in the late-spring and early summer of 1939. This 30-minute film tells the story of a family that inherits a guest house for animals. Hilarity ensues, at least according to the catalogue. Pandamonium was directed by the wonderfully named Widgey R. Newman and produced at a studio on Marylebone Road in central London. As its title suggests, the film was intended to exploit the massive popularity of Ming, a baby giant panda who was at the time the premiere attraction at London Zoo and something of a celebrity in her own right. Having appeared in a number of newsreels, Ming was said to have ‘as many fans as a film star’, so it is not surprising that Newman believed that the massive popularity she enjoyed at the centre of Britain’s first ‘panda craze’ could be profitably exploited (Birmingham Post, 11 Apr. 1939: 11).

Marylebone studio as it appears today

The Marylebone studio was converted from a disused building (either a hall or school, the record differs) attached to St Marks church. Newman, who mainly worked in low-budget shorts and ‘quota quickies’, had initially planned to make his film at Ealing studios but switched to Marylebone because of its proximity to London zoo, whose authorities wanted to minimise the amount of time that Ming had to spend travelling. The shorter journeys also reduced the insurance premiums that Newman had to pay for Ming’s transportation, although these still amounted to £440 (St Claire: 20). Ming was on set for only two hours per day – ‘very like a film star’ – in order to prevent her from getting so fatigued that she might not be able to appear before her adoring public at the zoo (Margrave: 6). There were also concerns for her health; the crew were obliged to wear ‘germ-proof masks and hospital smocks’, and the floor was sprinkled with ‘a special sawdust’ to improve hygiene (Aberdeen Evening Express, 1 Jun. 1939: 13; Herts. Mercury, 23 Jun. 1939: 6).

Ming postcard

Although she was by far the most famous, Ming was not the only animal who appeared in the film. Starring alongside her were

Remus, the wolf, Minnie, the tyra (from South America), Tony, Ming’s cousin, a lovely little chap with a pointed nose, and big round ears, who was far too nice for his official designation as a ‘common panda’, Nibby, the sea-lion, a pelican who didn’t have a name, Plassy, the penguin, called Percy by everyone and known in the film as Jimmy, and last and most important, George, the chimpanzee (St Claire: 20).

Kine Weekly was far less impressed with the humans in the cast, who included Zita Dundas, Hal Walters and Ley On, a Chinese-born actor and restauranteur who declined payment for his work on Pandamonium, but asked instead that his fee be used to buy bamboo shoots for Ming (Kine Weekly, 17 Aug. 1939: 25; Gloucester Citizen, 30 May 1939: 2). The zoo itself received a fee for letting Ming appear, having already sought to cash in on her fame by creating a range of panda-themed souvenirs including hats, handbags, toys and jewellery. An easter egg was produced containing Ming chocolates. Postcards bearing her image sold in record numbers (Yorkshire Post, 13 Mar. 1939: 8).

The pelican runs wild. Daily Mirror, 31 May 1939

Ming was said to have treated everyone on set with ‘Garbo-like indifference’, choosing only to interact with the keeper who accompanied her from the zoo in a private car (Margrave: 6). But any difficulties arising from her evident disdain for the crew paled into insignificance alongside the violent antics of her co-stars. Nibby, who also knocked Newman off his chair, ‘upset a lamp and bolted for the main studio door’ and could only be persuaded in front of the camera by bribery, in the shape of numerous fish (Northern Daily Mail, 2 June 1939:10). Plassy attacked Newman’s trousers; the pelican’s erratic behaviour forced Dundas to jump onto a chair; George pulled out plugs and played with switches (St Claire: 20; Daily Mirror, 31 May 1939: 5; Hodgson: 3).

Ming and George with the human actor Hal Walters. Picture Show, 24 June 1939

It is tremendously gratifying to hear of such disorderliness. The idea of these creatures running amok in a film studio is inherently amusing, mocking the hubris of humanity’s belief in its dominance by ganging a’gley the best laid schemes o’ men (although not mice, in this instance). Newman had made many films featuring animals, but this was the one that made him claim that he ‘would probably be grey’ by the time it was finished (St Claire: 20). Moreover, from our current perspective, forcing animals to perform tricks for the cameras can seem at best distasteful and at worst immoral; learning that Ming and the gang made life difficult for the crew makes them appear satisfyingly, and appropriately, rebellious. Even though the animals in Pandamonium were accompanied at all times by staff from the zoo, who were tasked with protecting their wellbeing, they were still encouraged to act anthropomorphically – as, indeed, they often were at the zoo – adopting ‘human’ behaviours for the benefit of the watching filmmakers and the pleasure of cinema audiences.

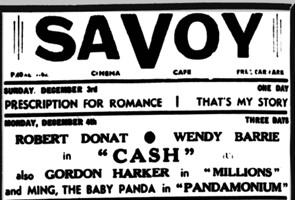

Advertisement for Savoy cinema in Folkestone, Hythe and District Herald, 2 December 1939, p. 6

Pandamonium was commercially released in late 1939 and played at venues around the UK. It received a number of positive notices. Befitting her status as star, Ming’s name was central to many cinemas’ promotional activities. By this time, and like many other youngsters living in London, she had been evacuated – in her case, to Whipsnade zoo in Bedfordshire. She was brought back to London in 1940. In 1943, she returned to the commercial screen in Strange to Relate (1943), another Newman short whose story bore more than a passing resemblance to Pandamonium. Ming’s popularity was such that her death in 1944 merited an obituary in The Times. Despite their artistic collaborations, Widgey Newman’s passing earlier the same year had not been similarly honoured.

References

Alan Hodgson, ‘Sea-lion’s film nerves’, Daily Herald, 31 May 1939: 3.

Seton Margrave, ‘Ming, the panda, is film star’, Daily Mail, 30 May 1939: 6.

Guy St Claire, ‘They told me themselves’, Picture Show, 24 June 1939: 20.