By Richard Farmer

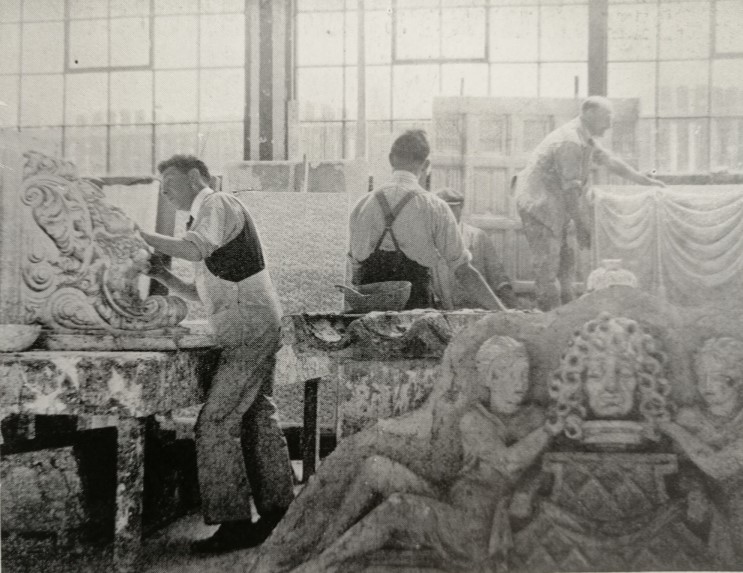

Cigarette card showing the plasterers’ shop at Shepherd’s Bush studio. The model of the clock tower at the Palace of Westminster was made for Friday the Thirteenth (1933)

When visitors were shown around film studios and the curtain was lifted on how films were actually made, they came to understand some of the processes that allowed the artificial to be passed off as real; had explained to them the part played in the creation of cinematic illusions by editing techniques and special effects and sound and make-up and lighting. But one site in particular tended to generate singular astonishment. As a guest at Denham observed not long after the studio opened in 1936, ‘the most fascinating of studio crafts is … that of the plasterer. In the spacious plasterers’ shop, every conceivable artifice and deception has its origin’ (RHC 1936: 31). Plasterers’ fabrications were tangible and seemingly solid, they were a deception that could be inspected at close quarters, scrutinised by a visitor’s incredulous eyes and disbelieving fingertips. As L. Hamilton Joscelyne found during a visit to Ealing in 1947, ‘realism in reproduction was astounding … “Brickwork” in plaster [was] almost indistinguishable from reality at the closest inspection’ (Joscelyne 1947: 3). Here, the joy of being deceived could be experienced in real time, in a place where the deception could be revealed and explained by a conjuror in dirty overalls who could show how ‘a substantial pillar – a veritable work of art – proved on investigation to be mere rags and plaster’ (RHC 1936: 31). This was an inherently practical magic.

The plasterer’s shop at Pinewood in Full Screen Ahead (1957)

Although decorative plasterwork had been used to build sets and make props pretty much from the start of the film industry, its use became more common after the introduction of synchronised sound technologies, due to its ability to partially absorb sound. Plasterers employed in British studios developed a reputation for high-quality work. In 1933, the plasterers’ shop at the British & Dominions facility at Elstree was said to be ‘staffed by the greatest living experts in this particular of make-believe and decorative manufacture’ (Winchester 1933: 390). That same year, plasterers at Gaumont-British’s Shepherd’s Bush studio turned out 30,000 tiles to be used in a recreation of the then recently closed British Museum underground station which featured in Bulldog Jack (1935). The same team also produced numerous props to fill the inside of the museum: ‘statuary, sculptured friezes and other exhibits … which includes armour, helmets, Chinese and Japanese costumes, swords, ancient weapons of war, etc.’ (Kinematograph Weekly, 27 Dec. 1934: 25). In many studios, art directors would consult with the head of the plasterers’ shop long before a production went on the stage, seeking their expertise on what would be the most efficient and effective way to design and dress a set. Any adjustments arising from their feedback to the film could therefore be integrated into the shooting script.

The plasterers’ shop at British and Dominions studio. (Kinematograph Weekly, 22 Nov. 1934: 51)

By 1940, some British studios were using more than 1,000 tons of plaster a year; Kipps (1941) alone required 45 tons to reproduce Edwardian Folkstone. A relative scarcity of wood in Britain – which also stimulated the early adoption of other studio equipment – meant that plaster was perhaps more important in UK studios than elsewhere. This importance became even more pronounced during the Second World War, when timber became scarcer and more expensive. Because most plaster used in the British film industry was domestically produced it was ‘one thing the Nazis can’t keep from us’ and so was used increasingly as a substitute for other materials (East London Observer, 30 Nov. 1940: 4). Indeed, it was not just wood that was replaced: as rationing schemes made it harder for British filmmakers to access food and fabric, plaster was used to recreate drapes and curtains and comestibles (Farmer 2011: 134-5). Ersatz edibles returned in October 1949 when a party was held at Isleworth studio to celebrate Glynis Johns’ birthday: ‘Stars, technicians, and studio hands [working on State Secret, 1950] gathered round a magnificent mouth-watering, beautifully-iced cake – a birthday gift from Douglas [Fairbanks Jr.]. Glynis huffed and puffed at the candles and daintily licked her lips. But the cake wouldn’t cut – “props” had made it from plaster’ (Liverpool Echo, 8 Oct. 1949: 4).

Plaster bananas being made for Men of Two Worlds (1946): ‘skilfully painted for the Technicolor cameras.’ (Kinematograph Weekly, 10 May 1945: 40)

The shortage of wood continued into the post-war period, exacerbated by the need to divert what was available towards the process of reconstruction. In late 1946, the Board of Trade announced a 75 per cent cut in the amount of timber allocated to the British production sector, a decision that was believed to risk an ‘almost complete stoppage of work in our film studios’ (“Radar” 1946: 4). So reliant did British studios become on plaster as a result that they had to eke out their supplies for fear that they would run out. The Independent Frame process developed at Pinewood was designed to reduce costs and counter shortages of basic filmmaking materials, including plaster, by using increased amounts of back projection (Kinematograph Weekly Studio Review, 19 Dec. 1946: 297). Some shops took to mixing plaster with other materials – the walls of a cottage seen in The Brothers (1947), for example, were 25 per cent sawdust (P.G.B. 1946: 36). More problematic was a ‘serious shortage’ of appropriately trained plastering staff, which could result in other workers standing idle for days at a time (“Radar” 1946: 4; Daily Film Renter, 9 June 1947: 10). Eventually, with sources of British labour exhausted, some additional plasterers were brought in from Ireland, although their lack of film-industry experience meant that it took them time to develop the skills needed for studio work (Kinematograph Weekly Studio Review, 10 July 1947: v).

The immediate postwar period was, then, the golden age of the British studio plasterer. It was not unusual for master plasterers’ names to appear in trade publication such as Kinematograph Weekly and some 250 plasterers briefly went on strike in the summer of 1947 in protest about a regrading of wage rates that would have seen studio carpenters and painters paid as much as they were. So central were plasterers to British film production at this time that the walkout threatened to close the studios altogether; it was only the possibility that other industry employees might lose their livelihoods that persuaded the men to return to work and agree to industrial mediation.

The Eros statue in October Man (1947)

Studio plasterers were also often called upon to compensate for the pronounced impact that the war had had on the British cityscape. When Two Cities wanted to create an authentic London backdrop for October Man (1947), it found that it had to reproduce the Eros statue that traditionally stood in Piccadilly Circus, as the original had been taken down for safekeeping at the start of the war had not yet been re-erected. A replica was made with the permission of the London County Council:

This is how it was done. Arthur Banks, the head of the Denham Plaster Shops, visited County Hall, where “Eros” now reclines on sacks and sand-bags. He measured the statue and made an exact model of it, from which moulds were made, and a life-size replica of “Eros” was cast in plaster.

In the film the statue, which appears for only a few seconds, is filmed from a low angle in a not-entirely-successful attempt to hide the fact that it is being shot in the studio rather than on location. Yet there were concerns that because the entirety of the statue’s weight (approximately 250 kilograms) rested on one leg, the plaster might not be able to bear the load. This had not been a problem for the original, which had been cast in aluminium (Comet 1947: 2). As it transpired these concerns proved groundless. The shot was successfully accomplished and by the time that October Man was released, Eros was back in position, allowing the film to appear suitably up-to-date.

As a local newspaper report made clear, the film Master of Bankdam (1947) features a plaster foundation stone that was originally inscribed ‘November 1888.’ However, the sequence in which it was used was filmed on the lot at Walton-on-Thames studio in high-summer, when the trees visible in the background of the shot were in full leaf and every plant looked lush and verdant. This discrepancy caused ‘slight consternation until the plasterer crossed the lawn with his “stone filling” and cut a new inscription.’ While the remedial work was said to have maintained the unit’s ‘infallible record,’ it is not difficult to spot the alteration in the final film (Blackburn 1946: 2).

Foundation stone in Master of Bankdam (1947) featuring on-set alteration

Two years later, the summer climate posed a different kind of problem for the crew working on Ealing’s Passport to Pimlico (1949). Exteriors for the film were shot using a large outdoor set built on a bombsite in Lambeth, with plasterers ‘counterfeiting bricks and mortar in lath and plaster’ and working alongside riggers, carpenters and painters to create a convincing replica of a street in west London: ‘These boys, who make bricks and stones out of hessian and a puddle of damp powder, deserve the greatest possible admiration. Even at two yards range you cannot distinguish one of their bricks from one straight from an LCC housing project.’ The weather, however, was foul and caused numerous delays: ‘During the past couple of weeks [the crew] have passed through the varying stages of confidence, hopefulness, anxiety, disappointment, baffled rage and sheer resignation on account of the grey skies and rain’ (‘F’ 1948: 24). A dry, sunny day was, it transpired, about the only thing that studio plasterers couldn’t rustle up at a couple of hours’ notice.

References

Harold Blackburn, ‘Artist mill-hand in a film studio,’ Huddersfield Daily Examiner, 20 August 1946, p. 2.

Comet, ‘Stardust’, West London Chronicle, 28 March 1947, p. 2.

‘F,’ ‘British studio news,’ Kinematograph Weekly, 22 July 1948, p. 24.

Richard Farmer, The food companions: cinema and consumption in wartime Britain, 1939-45 (Manchester University Press, 2011).

L. Hamilton Joscelyne, ‘“Shooting” a film,’ Newsman Herald, 13 June 1947, p. 3.

P.G.B., ‘Studio news and views,’ KW, 22 August 1946, p. 36.

“Radar,” ‘Radar, news commentator, reports…’, Gloucestershire Citizen, 4 November 1946, p. 4.

RHC, ‘Technicians visit to Denham,’ Kinematograph Weekly, 30 July 1936, pp. 31, 36.

Clarence Winchester (ed.), The World Film Encyclopedia (London: Amalgamated Press, 1933), p. 390.