By Richard Farmer

Norman Loudon

In late 1938, Norman Loudon, Managing Director of Sound City (Films) Ltd., issued an underwriting prospectus in the hope of drumming up £125,000 to invest in a new venture at his company’s studios at Shepperton (Williams 1938). Loudon had been the driving force behind the creation of the Sound City facility, which opened in 1932 and was built on the grounds of Littleton Park House in Middlesex, about 15 miles south-west of central London. In late 1938, British film production was beset by one of its periodic slumps and Sound City was feeling the pinch: ‘Five films have been turned out at Sound City this year, as compared to 30 last year. Only 25 persons are employed at the studios now, compared with 700 last year’ and in the same period turnover dropped by some £94,000 (Hollywood Reporter, 14 Nov 1938: 2; Kinematograph Weekly, 1 Dec 1938: 3). Loudon hoped to diversify revenue streams and offset losses in the filmmaking part of his business by generating income even when the studio’s seven sound stages weren’t occupied.

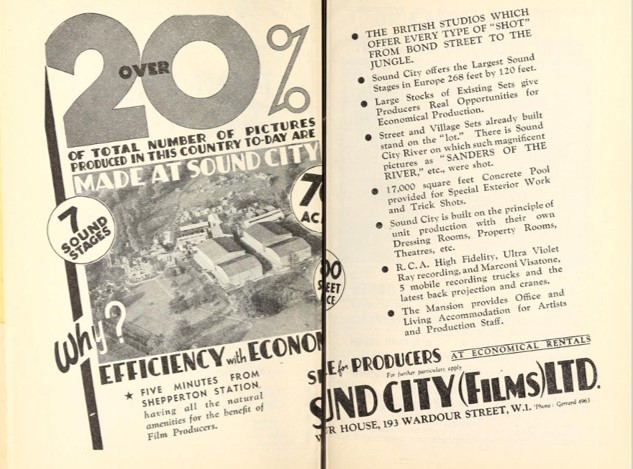

Advertisement for Sound City studios, Kinematograph Year Book, 1937

Loudon landed on the idea of opening zoological gardens and a pleasure park. This proposition was met with incredulity by many sections of the British film industry. One trade paper pooh-poohed the idea, claiming it as nothing more than a silly rumour related to a proposed ‘animal picture’, while another noted that the prospect of wild animals roaming around Sound City was ‘regarded as very much of a joke’ (Stroller 1938; Tatler 1938b). In addition to being amused, the trade was also slightly concerned. Not, it seems, by the danger posed by lions or penguins breaking free from their enclosures and terrorising visitors, actors or crew, nor by the ethical considerations of keeping wild animals in captivity solely for the contribution they might make to an ailing studio’s balance sheet, but rather by the damage that the zoo might do to the prestige and reputation of the production sector (Tatler 1938c). For an industry still craving that most British of vices, respectability, the Sound City Zoo and Wonderland was an unwelcome reminder of film’s rough and ready origins, especially as the money-making scheme was quite explicitly linked to economic instability of a kind that most in the industry hoped was behind them.

Littleton Park house and estate: Daily Film Renter, 13 June 1934

Loudon evidently didn’t care. As he saw it, a zoo was pretty much a license to print money: ‘all you need are the animals, and the patrons, and everything in the garden’s lovely’ (Tatler 1938a; also Williams 1938). In order to get patrons through the gates, Loudon planned the erection of numerous signposts around the country, telling drivers how far they were away from the Sound City Zoo (Threadgall 1994: 23). These markers were to be known as ‘The Sign of the Giraffe,’ and if Loudon didn’t pass that name on to the Sound City scenario department as a title for one of the cheap ‘quota quickies’ churned out at his studio, he missed a trick.

Despite the expected profits, the Sound City Zoo was to act as an adjunct to the studio, not replace it entirely. Indeed, it was proposed that the zoo would be designed so that ‘scenes of animal life in natural surroundings can be made available for filming’ (Manchester Guardian, 30 Nov 1938: 16). Or, as the Daily Film Renter’s Tatler put it: ‘you won’t have to go to Africa to make your Tarzan pictures in the future – a few ropes hanging from the trees among the denizens of the Sound City Zoo, and you’ll be … Tarzan to the life’ (Tatler 1938a). The zoo would also have made Sound City an attractive place to educational filmmakers. The hotel and restaurant that formed part of the zoo development would also have a dual purpose – offering beds and refreshments both to those using the ‘new rural resort’ and those filming at the existing studio (Manchester Guardian, 30 Nov 1938: 16). It is not clear how the company would have kept the noise made by visitors to and inhabitants of the zoo from interfering with exterior filming at Sound City, which remained one of the few profitable parts of the studio in 1938-39 (Carter 1939: 349).

Model of proposed Sound City zoo and wonderland (Threadgall 1994: 22)

Loudon’s plans would have seen approximately half of the 60-acre Sound City estate turned over to the new visitor attraction (Tatler 1938a). As it was, a scale model of zoo and pleasure park was built which covered ‘most of the … floor’ of one of the studio’s stages (Threadgall 1994: 21). This model would have been developed under the watchful eye of Alan Best, a trained sculptor who had worked for the Wedgwood ceramics company before becoming assistant curator at Regent’s Park (now London) Zoo, who had been engaged to develop plans for the zoo. Details of what was proposed are contained in Jill Armitage’s Secret Shepperton:

Using the skills and artistic ability of the Sound City craftsmen, fifteen differently themed areas were to be created, showing 100 different species of animals and birds against vividly realistic backgrounds of forests, icebergs, tropical rivers and jungles. There was to be a spectacular circus, Noah’s Ark and children’s paradise with thrills and amusements never before experienced.

The make-up of the menagerie is unclear, although one contemporary report noted, admittedly in a joking tone, that ‘troops of rhinoceri, zebras, giraffes, lions, and so on and so on’ would soon be seen drinking from the river that ran through the Littleton Park estate (Tatler 1938a). I have not been able to find out exactly which ‘thrills and amusements’ were to have been offered, so it remains unclear whether they would have taken inspiration from the site’s status as a functioning studio let alone sought to exploit any of the films that were made there. That said, it’s certainly possible to imagine rides and attractions linked to such titles as The Ghoul (1933) or Colonel Blood (1934).

Would visitors to Sound City Zoo and Wonderland dare enter The Ghoul’s ‘house of mystery’? (IMDB)

Whether the Sound City Zoo and Wonderland would have constituted some form of proto-Disneyland is, though, a moot question as the scheme didn’t proceed beyond the initial planning stage, and so constitutes another example of ‘unbuilt infrastructure’ of the kind that the STUDIOTEC project has regularly unearthed (see my article on Esher here and Tim Bergfelder and Eleanor Halsall’s blog on unbuilt German studios here). The ‘uncertainty brought about by the international situation’ in the months before the outbreak of the Second World War proved ‘a great hindrance in the furtherance of the plans’ (Kinematograph Weekly, 8 June 1939: 13). As late as June 1939 Sound City was still professing its desire to proceed, but the requisitioning of the studio by the government finally put the kybosh on the project. Studio employees who might have used their skills to create convincing animal habitats were instead put to work for the war effort: Sound City turned out dummy Wellington bombers at £225 a go, used to populate decoy airfields designed to draw enemy fire away from the real thing (Dobinson 2000: 24-8).

Sound City did eventually become home to some big game, however. When the studio returned to filmmaking purposes in 1946, it briefly became the home of the production and distribution company British Lion.

Credit from Bonnie Prince Charlie (1948), made at Shepperton and distributed by British Lion

References

Jill Armitage (2022). Secret Shepperton: England’s Hollywood. Stroud: Amberley.

A. L. Carter (1939). ‘British production’, in Kinematograph Year Book, 1939. London: Kinematograph Publications.

Colin Dobinson (2000). Fields of deception: Britain’s bombing decoys of World War II. London: Methuen.

Stroller (1938). ‘Long shots,’ Kinematograph Weekly, 25 August: 4.

Tatler (1938a). ‘Wardour Street gossip’, Daily Film Renter, 2 November: 2.

Tatler (1938b). ‘Wardour Street gossip’, Daily Film Renter, 2 December: 2.

Tatler (1938c). ‘Wardour Street gossip’, Daily Film Renter, 7 December: 2.

Derek Threadgall (1994). Shepperton studios: an independent view. London: BFI.

L. D. Williams (1938). ‘Sound City zoo’, Daily Mail, 1 November: 2.

One thought on “Shepperton world of adventures: Sound City Zoo and Wonderland”