By Sarah Street

On Sunday 9th February 1936 film producer Herbert Wilcox lay awake in the early hours of the morning at his home located high up on Deacons Hill Road overlooking the British and Dominions’ Imperial Studios he’d founded at Elstree in 1930. He recalled with horror: ‘I could not sleep. I got up and wandered over to the window. A red glow filled the sky. I looked at the source. It was a huge fire at the studios – my studios!’ (Wilcox, 1967: 109). Wearing his pjs under an overcoat, he rushed to the blazing site, rescuing films stored in the vault. Other recorded witnesses to the disaster were cinematographers Jack Cardiff and Ronald Neame who also saw the fire’s glow from a house where they were lodging opposite the studios (Cardiff, 1996: 33-5). They rescued cameras and even shot some footage (believed lost) of the fire as it destroyed three stages, 44 dressing rooms, 24 offices, three reception rooms, a converting room, and a wax shaving room (used in sound recording). British International Pictures (BIP) were also affected, losing three of their adjacent nine stages at Elstree, the central recording dept, and 36 dressing rooms and offices. About 1000 workers were reported as being temporarily thrown out of work by the disaster (Illustrated London News, 15 Feb 1936: 1). A Gaumont British newsreel captured aerial shots of the fire.

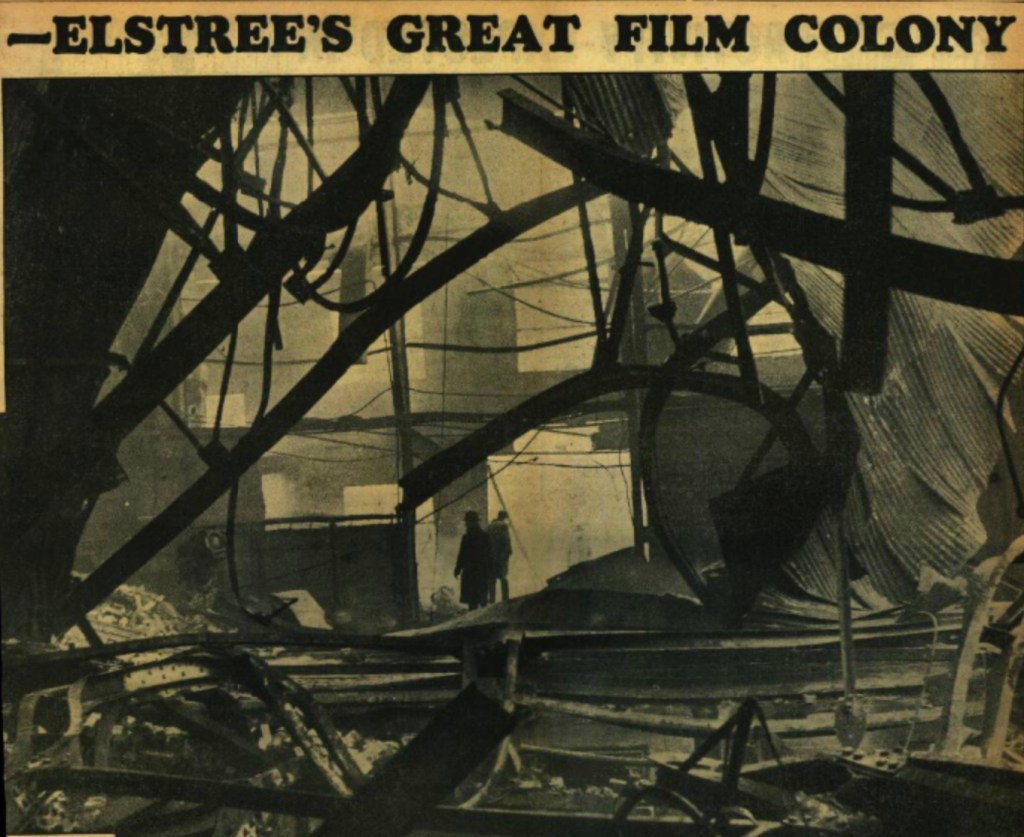

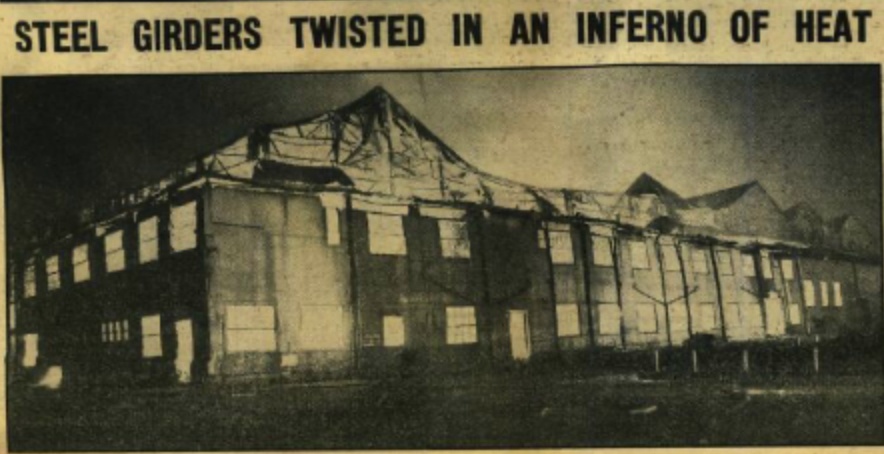

Photographers also recorded the devastation caused by the blaze. Falling debris, twisted steel, smouldering ash, stricken girders and skeletal-like wreckage, made for dramatic images which conveyed the fire’s full horror.

Anna Neagle and band leader Geraldo, Daily Mirror 10 Feb 1936: 14

Devastating destruction, Daily Mirror 10 Feb 1936: 15

Shattered roofing, Daily Mirror 10 Feb 1936: 15

Aerial view, Daily Mirror 10 Feb 1936: 14

The fire’s ‘sensational’ effects

The press reported the fire’s ‘sensational’ effects (Kine Weekly, 13 Feb 1936: 13). Mercifully there were no serious injuries except for a fireman who fell and injured his arm and two other firemen reported as injured by falling debris. Anna Neagle, Wilcox’s film star wife, and actor Sydney Howard were seen searching the debris ‘among which there stood out grotesquely patches of costumes, pots of grease paint and the fluttering pages of scenarios’ (The Daily Herald, 10 Feb 1936: 1). Other casualties were Clive Brook’s wig collection and a treasured make-up box given to American actress Helen Vinson by her mother, as well as her entire wardrobe. Mary Carlisle, an American actress who had been brought over by producer Max Schach to star in Love in Exile (Alfred L. Werker, 1936), was never able to read her fan mail which was consumed by the flames. An ‘inconsolable’ Wilcox said the fire was ‘one of the biggest disasters the British film industry has ever experienced’ (The Daily Herald, 10 Feb 1936: 2). But all things considered, and despite £450,000 worth of damage, current productions were only held up for a short time. The studios were covered by insurance and some productions, such as Love in Exile, were relocated to other studios with available space. Wilcox thereafter produced films at the newly opened Pinewood Studios. The support buildings in Borehamwood that remained after the fire were sold off to various companies including Frank Landsdown Ltd, which opened a film vault service. The Rank Organisation bought the music stage to produce documentaries; this later became HQ of the film and sound-effect libraries. Despite this recovery and relocation, Wilcox remembered the studios destroyed in the fire fondly as his ‘lucky’ stages where Jack Buchanan, Anna Neagle and Elisabeth Bergner had made film history (Wilcox, 1967: 109). Brewster’s Millions (Thornton Freeland, 1935), a musical comedy starring Jack Buchanan, was filmed at the studios, as illustrated by this pic of the film in production.

Filming Brewster’s Millions at Elstree, 1935

British and Dominions’ valuable negatives weren’t damaged, and it was reported that ‘the financial books and records have been preserved’ (Kine Weekly, 13 Feb 1936: 13). We at STUDIOTEC would of course love to see the latter, if indeed they survived other subsequent dangers.

Heroes and a heroine

Neighbouring BIP studios had their own fire brigade, founded by studio manager Joe Grossman. Although their daily drill was seen as something of a ‘joke’ by studio employees, they were mightily grateful for it when disaster struck (The Daily Herald, 10 Feb 1936: 2). No one knew exactly how the fire started but the flames were first seen by a night fireman who alerted the BIP brigade which responded rapidly to the disaster. A water screen raised between the British and Dominion stages and BIP’s nearby main building restricted the fire’s rapid spread. The timing of the fire, and the brigade’s swift action surely saved lives if not Wilcox’s beloved studios.

The BIP Fire Brigade, 1936. Hertfordshire archives and local studies

Heroism was also evident involving a perhaps unexpected feline resident. A cat belonging to one of the studio firemen was seen running from the fire carrying a kitten she’d rescued in her mouth. The cat’s bravery was celebrated as ‘heroine’ of the fire (The Daily Herald, 10 Feb 1936: 2).

Studios as dangerous environments

Film studios were highly dangerous environments. Other cases had more serious consequences such as two men being killed in 1930 in fires respectively at Twickenham and Gainsborough Studios. Another major fire occurred at Twickenham in October 1935. Celluloid was of course highly flammable, and the dangers of studio fires increased considerably after the introduction of sound because ‘the heat of studio lighting and the insulation used for sound proofing made for a lethal combination’ (Jacobson, 2018: 23). These dangers meant that fires also occurred in Hollywood’s studios as well as in other European studios. In 1935 the Cines studios in Rome were destroyed by fire. Film companies tended to underplay the risks involved in studio production, and health and safety awareness was far from rigorous. Employees suffered uncomfortable, even dangerous physical effects from the heat generated by arc lamps, heavy machinery, hazards in studio workshops and during set construction, and the creation of highly combustible fake fires as studio effects. Damage was also caused at Denham in March 1936 when the studios were being constructed, and a few months later a fire destroyed a small studio at Southall owned by Fidelity films. These incidents drew attention to how studios could better protect themselves, as a trade manual commented: ‘The number of studio fires that have occurred has directed attention to various types of extinguisher apparatus, and the sprinkler system is in common use in all modern erections. Among the experts who cater for every conceivable form of fire risk is the Pyrene Co., who will give details of insurance rebates, methods of extinction and details of all approved extinguishing media’ (Kine Year Book 1937: 290). Just a month after the fire a fireproof paint called ‘Porcilla’ was demonstrated at Elstree (Kine Weekly, 19 March 1936: 58). Nevertheless, film studios remained hazardous workplaces, and the skills and equipment required to both anticipate and deal with them effectively took a long time to become key priorities. Later at Elstree set designer Wilfred Arnold was known as the ‘demolition king’ because of the ingenious way he designed and constructed pristine, perfect sets audiences would then see destroyed as onscreen spectacle, as they were in British National’s The Three Weird Sisters (Daniel Birt, 1948).

Staged destruction in The Three Weird Sisters

While the destruction of sets was an acceptable activity for such purposes and when their re-use wasn’t practicable, this happening in real life and on a much larger scale was a reality employees lived with each day they entered the studios.

References

Jack Cardiff, Magic Hour (London: faber and faber, 1996).

The Daily Herald, 10 Feb 1936: 1, 2; 11 Feb 1936: 9.

The Daily Mirror, 10n Feb 1936: 14-15.

Illustrated London News, 15 Feb 1936 (cover).

Brian R. Jacobson, ‘Fire and Failure: Studio Technology, Environmental Control, and the Politics of Progress’, Cinema Journal, 57:2, Winter 2018: 22-43.

Kinematograph Weekly, 13 Feb 1936: 4, 13, 35; 19 March 1936: 58.

Kinematograph Year Book, 1937.

Herbert Wilcox, Twenty-Five Thousand Sunsets (London: Bodley Head, 1967).