By Sarah Street

Film studios were communities of workers who established close bonds through the collective enterprise of film production. They employed many diverse occupations, including canteen employees, art directors, costume designers, hairdressers, secretaries, publicists, electricians, and carpenters. Establishing a sense of community was important, especially when working conditions could be pressured and intense, with each production throwing up new challenges, especially when working within tight budgets and time constraints. Surviving documentation on the social lives and activities of film studio employees is rare to find, even though we know that several British studios produced in-house magazines. One such example is the Pinewood Merry-Go-Round magazine, published by Independent Producers from August 1946 to December 1947. This publication provides a rare glimpse into how studio employees bonded through sports and social clubs, music and film groups, organising a Christmas pantomime, art exhibitions, sharing studio gossip and reports on particular issues of concern such as transport to work and long working hours. At a time when paper was still rationed, the magazine was rather lavishly produced, with a glossy colour cover design.

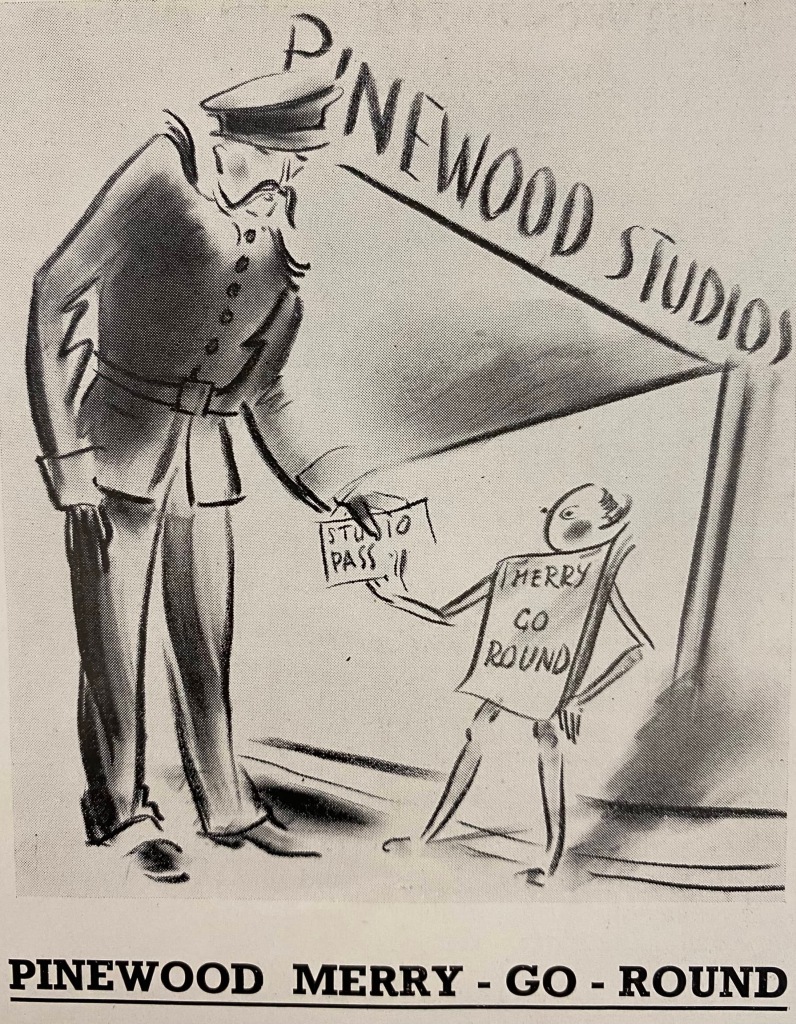

The first issue’s editorial declared the Pinewood Merry-Go-Round’s purpose as ‘an interesting, informative and amusing magazine for all Pinewood people, written and illustrated by them’. It stated further that: ‘Nothing will be included that is not of interest to Studio people themselves. It must be remembered however, that copies are bound to find their way into the hands of “outsiders”, so we must make every effort to do ourselves justice’. The magazine was posted free of charge to every member of the studios once a month, and the Acting Editor Joy Redmond, a film publicity director, called for contributions: ‘We need short stories, cartoons, details of any hobbies you have, technical articles that are of interest to us all; sketches, amusing incidents and bits of gossip that are always happening in the studios and hundreds of other items that will make the magazine representative of you all’. Redmond was succeeded as Editor in October 1946 by journalist Tom Moore who occupied the role for the magazine’s short lifetime. The magazine provided a ‘pass’ into the studio like no other, as captured by this cartoon printed in the first issue.

By November 1946 the magazine had established a clear role for itself, its success leading to a broadening of its scope, as noted in the editorial: ‘There can be few industries which call for greater team-work than ours. The more a film worker knows about the broad principles of the other man’s job and what he is trying to get at, the greater will be his own contribution to the general efficiency of his studio and ultimately, of course, to his own well-being’. Both unions and managers were represented, the former writing columns and reports on key issues such as poor transport links to and from the studio and working hours, while J. Arthur Rank’s involvement as President of the Music, Art and Drama Group reflected his enthusiasm for such activities and the magazine’s role in helping to spread knowledge about what everyone did in the studios. The transport issue rumbled on over several issues and was linked to the ‘very poor’ response to an appeal in October 1946 for those interested in forming a Social and Sports Club. The transport problem was blamed since employees were worried about getting home after Club events. Rank promised to secure better bus transport and appointed a Transport Minister ‘but the fact remains that the transport position is unsatisfactory’, and some employees were in favour of Rank building houses near Pinewood. One carpenter wrote a letter to the magazine on the subject. The journey to work took him two and a quarter to two and a half hours and the same time to get home: ‘Being on night shift I have to leave home at 5.30pm at the latest and do not get back until after 10am. At the most, I get in about 5 hours sleep. These travelling times are in normal weather conditions. With the present winter snow, I realise that I just could not make it, so stop away. I have hunted high and low for other accommodation nearer Pinewood, and during the past year even slept in a tent in the orchard by the gate. Is it any wonder that I arrive at work tired, sometimes (very often, in fact) late and lost time through being indisposed. Could not the studio provide somewhere for long-distance workers to sleep? It would repay them many times over in time saved. I am a keen sportsman and would wholeheartedly support the Sports Club, but cannot under the present conditions. I would like to add that I like my job and find D. & P. studios the best of them all – having tried the lot’. However others, particularly workers in the Art Department, opposed living very close to the studios. They were not impressed with the Hollywood model or living with the same people they worked with day in day out. A humorous poem captures something of the strong views and emotions involved in the housing issue.

Regular features included the Pinewood log and gossip section. One item reported: ‘The Fitting Room cat recently produced four kittens who considered the lathes, drills and milling machines ideal playthings. General relief is now felt by all in the Shop – the kittens have been distributed among less dangerous departments, with their tails intact!’ Another shared a welcome by-product of a recent production: ‘Anybody feeling that the English summer has let them down, can borrow tropical clothes and sit under the Bamboo trees that have been made for Black Narcissus. Rumour has it that the men working on these models have been nicknamed “The Bamboo-zle-ers!”’ Some employees were highlighted in special reports such as on Ben Goff, General Foreman of Messrs. Boots, engaged in construction work in the studios. Goff had been employed as a brick-layer foreman when Pinewood was being built in 1934. He was back at Pinewood in October 1946 supervising construction work with four colleagues who worked with him when the first bricks were laid in the studios. He recalled that the first brick was laid by Mrs Spencer Reis, wife of Charles Boot whose engineering and building company designed and constructed the studios following Boot’s purchase in May 1935 of extensive parkland and Heatherden Hall, a country mansion, located at Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire. An early image shows the studios, Heatherden Hall and gardens shortly after operations had commenced.

In November 1946 veteran film producer Cecil Hepworth visited Pinewood and was shown around by an old friend. The report detailed how they discussed the export of British films, a topic the magazine reflected on by publishing choice quotations from American publications about the British films spearheading Rank’s post-war export drive. Technicians who had worked in the studios for a long time were applauded, such as Frank Ellis, 1st Camera Assistant on Green for Danger (1946), the first film to re-open the studios, who had worked on the first camera ever to turn at Pinewood. Before the studios were officially opened in 1935 an acoustic test was arranged by the Hon. Richard Norton, and Ellis came over from Elstree to assist. Another ‘old inhabitant’ of Pinewood was Robert ‘Reg’ J. Blackburn, Chief Electrician. Reg worked at Pinewood from the day the studios opened until they were closed during wartime.

Pinewood’s social calendar included the Paint Shop’s outing to Southend in November 1946, and in July 1947 there was a joint Denham and Pinewood day trip to Margate. The party travelled in coaches and the attractions included lunch at ‘Dreamland’, tea and an all-star variety show in the evening.

The magazine regularly reported sports and other competitive activities. The darts section of the Sports and Social Club had the biggest following. A competition held in May 1947 involved a stars’ team playing The News of the World’s visiting team. Cecil Parker threw the winning dart that won the competition for the stars. A report noted that the Pinewood ‘Sparks’ football team would be grateful for more support for their matches because when they played Denham’s ‘Sparks’ team on their home ground of the Pinewood lot in December 1946, there were only two supporters present. Denham fans were better represented, and they beat Pinewood by six goals to five. Pinewood’s team colours were white shirts with green cuffs and collars and the three pine trees of D&P’s trademark on the pocket. A British Film Industry Sports and Gala Day was held at Uxbridge RAF Stadium in September 1947. Ealing won overall, and the report noted ‘many exciting races’ took place. The runners-up were Technicolor, with Denham third, and Pinewood, one point behind, came fourth. A further note comments on the event’s convivial, social function: ‘The prevailing spirit of friendly rivalry encouraged competitors and spectators alike to meet and mix with colleagues from other studios’.

Occasionally the magazine provides glimpses into the operations of other studios. An article on Marc Allégret, a French director who arrived in Pinewood straight from a French studio in January 1947 to direct Blanche Fury, is a case of particular interest to STUDIOTEC. He recalled how in France working hours were restricted owing to an acute shortage of electrical power. This meant increased night work when more power was available because of the drop in industrial and domestic consumption. Allégret compared current conditions in French studios with those prevailing at Pinewood. He observed how when faced with a ‘rain’ shot British electricians didn’t have to worry over the very real possibility of someone getting a severe shock should the water contact aged and worn cables that should have long since been scrapped. He also claimed that Pinewood’s floor units were not forced into inactivity by the acute shortage of equipment affecting studios in France. Another difference was lack of heating in French studios which meant cameramen were forced ‘to add insult to injury by making their shivering subjects suck ice cubes during “takes” in an effort to minimise fog caused by warm breath meeting frost-cold air’. Despite these problems Allégret noted that the French studios were still making good pictures, referencing the success in London of Les Enfants du Paradis (1945). Allégret had worked in the UK previously on trick shots in the ‘flying carpet’ sequence in The Thief of Bagdad (1940). The report closed with an interesting comment on studio methods, and the exchange of ideas between workers and managers: ‘The equipment and material here has impressed him tremendously – but equally so did the men who use it and their methods. Soon after he arrived here Marc attended a meeting of the Studio Works Committee; he came out full of enthusiasm for what to him, was a new and thrilling departure in the business of picture making. In French Studios there exists no such system whereby the employee and employer can meet for the express purpose of exchanging ideas for the improvement of their industry. He has already written to France, urging them to adopt a similar system in studios over there. Perhaps this is the forerunner of the interchange of talent and ideas he so earnestly hopes to see develop between his country and ours’. This comment reflects the great instability in employment for French technicians in 1947-48 when there were mass redundancies. Workers were in discussions with unions, but the quick turnover of employment from studio to studio meant it was difficult to establish dialogue with managers in terms of improving working methods.

In December 1946 George Busby, production manager and assistant producer for The Archers reported on looking for locations in France and Italy. Busby went to Cinecittà when it was being used as a camp for displaced persons. He found the studios in Rome to be very well equipped ‘although the employment of tubular scaffolding for set building has only just been introduced. Hitherto wood has been in plentiful supply’. This was considerably later than in Britain, as reported in a previous blog on tubular scaffolding, and where there was a severe timber shortage in 1947. In Nice Busby considered the studios to be well-equipped, ‘with sets of a quality second to none’, and he witnessed the first colour film in the post-war period being processed in Agfacolor. In Paris, Busby visited Pathé and the old Paramount studios. Another issue featured an article by British matte painter and storyboard artist Ivor Beddoes on Arab films. Such incidents and reports opened-up the magazine’s content to international film news.

The magazine was well-produced, featuring cartoons by studio employees. One cartoon published in the October 1946 issue was titled ‘Pinewood Phantasmagoria!’

In the same issue ‘The Art Director’s Dilemma’ depicted a playful comment on perspective.

In December 1947 the last issue of the Pinewood-Merry-Go-Round was published. The reasons given were continuing paper shortages and the amount of time it took to produce each issue. In the context of continuing post-war austerity the editors decided to cease publication because: ‘We cannot argue that [the magazine] is really essential’. This verdict was not without regret since its purpose had helped to ‘create a good spirit all round’ the studios, and ‘we can look forward to its return when the crisis is over’. This didn’t happen, so the existing record cannot be compared with a later publication from Pinewood. For the years 1946-47 the magazine however provided many insights into what it felt like to work in a studio and how workers socialised outside of work hours. As well as documenting a wide range of activities the magazine had drawn attention to novel uses of Pinewood’s spaces such as an Art Exhibition staged in the South Corridor, and training for a forthcoming boxing tournament carried out in a marquee erected in the paddock area. The convivial tone of the publication reflects something of studio employees’ energy, enthusiasm and curiosity about each other’s lives and work in the shared enterprise of British filmmaking at a crucial time in its history.