By Eleanor Halsall

My working life began as a translator of patents, designs and trademarks with a London firm located near the original Patent Office in Southampton Buildings. Inside this venerable building, the vaulted, balconied library was crammed with books, antique and new, tracking the history of science, invention and discovery. Nevertheless, its dictionaries struggled to keep ahead of countless neologisms that sought to encapsulate the latest technology, often leaving the translator to coin new terms with the appropriate specialist.

The Patent Office Library in 1902. Credit: RIBA Collections

The history of film is also the history of ideas and inventions, and patents and designs can provide an important source of information about how the industry was developing at any given period and how filmmakers were constantly engaged with ideas to expand and improve upon the medium of the moving image (see Sarah Street’s blog post on the making of Black Narcissus). The proliferation of patents across the global film industry during the transition to sound film is a topic that has been amply debated in the historiography, but patents, and their close cousins, designs, continue to provide useful insights into the numerous ways in which film studios were developing and adapting as they encountered new technologies and improved working practices.

The patent document itself follows a conventional format. Its specification typically describes the current position of the science (state-of-the-art or Stand der Technik) before introducing the applicant’s original idea or invention, and the manner in which it claims it can address the problems that it has identified. It then lists the individual claims and follows up with any illustrations required to support the application’s novelty – or simply to throw a lifeline to anyone struggling to visualise text such as ‘the angle member which so extends at one end is fixed to one stancheon, and the angle members of the other girder which extend from the opposite end are fixed to the other stancheon’ (GB 335045, Improvements connected with scaffolding, 5 September 1929) which starts to sound like an invocation to dance! Beyond the specification – at least some of which will probably appear impenetrable without the appropriate scientific knowledge – these legal documents might also be read as historical accounts reflecting the influence of politics and commerce, social attitudes and fashions, and much more besides.

As assets that protect the applicant’s invention for a specified period (usually 20 years), patents hold a commercial value for the owner to grant a licence for the idea to be manufactured or implemented. Ufa itself had a large department dedicated to intellectual property and was avid in defending its inventions; evident from correspondence about the studio’s disagreements with Joe May (BArch R 109-I/1027b, 18 August and 23 September 1929), Klangfilm and others. At the end of the Second World War, patents were appropriated as ‘spoils of war/Kriegsbeute’, along with machinery and materials, partly to provide insights into Germany’s technological know-how (Gill/Mustroph, 2015) but also to give commercial advantage to the recipients. Among these were patents belonging to Agfa which were released so that other countries could immediately benefit from German advances in colour technology.

A significant number of studio-related patents focus on aspects such as the hardware for evolving technologies for sound, colour and television, or the chemical composition of film stock, as in this snappily-titled Agfa patent: ‘Process for the pre-treatment of hydrophobic photographic substrates for coating with hydrophilic colloidal layers’ from 1958 (‘Verfahren zur Vorbehandlung von hydrophoben photographischen Schichtträgern für den Beguss mit hydrophilen Kolloidschichten’, DE1086998).

Other patents may appear more accessible to a lay public, at least by their evocative titles if not by their scientific explanation. Take, for example, German patent DE488567 which explains how to create snowy landscapes for filming (‘Szenische Einrichtung zur Darstellung von Schneelandschaften’, 12 December 1929); or Austrian patent number AT116265 telling filmmakers how to create ghostly images on screen (‘Darstellung von Geistern u. dgl. mystischen Gestalten für Bühne und Film’, 10 Feb 1930). Even though the science is complicated, they have an accessible feel about them. Other patents describe devices or systems to facilitate studio work, for example Klangfilm’s patent outlining a communication system between director and the various sound engineers (‘Signaleinrichtung für die Verständigung des Regisseurs, des Tonmeisters und des Tonmechanikers bei Tonfilmaufnahmen’, DE669704, 10 May 1934); or elements of tubular scaffolding, cited above, which became an essential component in film studios (see Richard Farmer’s blog post). Eugen Schüfftan’s famous technique of using models and mirrors to recreate cities, successfully employed in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and subsequently used extensively by the British film industry, was the subject of several patents throughout the first three decades of the twentieth century.

Peter Schlumbohm described a magnifying mirror which actors could hold to check their make-up was being evenly and appropriately applied: ‘An essential requirement for black and white film and one which will become even more significant with colour film’ cautioned the specification (‘Toilettenspiegel’, DE504081, granted 17 July 1930). Using the correct make-up was a concern that led Alexander von Lagorio, Ufa’s colour specialist, to devise a process to measure the levels of florescence in individual make-up formulas to ensure compatibility with various film stocks so that faces were not recorded in unexpected colours and teeth did not appear black! (‘Verfahren zur Auswahl geeigneter Schminken und Zahnlacke für die Zwecke der photographischen und kinematographischen Aufnahme’, DE735317, 8 April 1943).

One of a tiny handful of patents applied for by women in the early decades of film production was Helene Pächter’s invention (‘Kartei, insbesondere für Filmszenen’, DE537447, 15 October 1931). This describes a card system to record and locate scenes from films, specifically offcuts that had been rejected from the original film, but that might be suitable for insertion into other films, or for back projection purposes. Meanwhile the subject of back projection itself was the subject of multiple patents across Europe.

The Normaton patent of the title is of interest for two reasons. First and foremost, because of its innovative (if somewhat unwieldy) proposal for managing and transporting generic film sets, but also because of the questions it provokes about its fate and the extent to which there was at least commercial, if not political, involvement in its demise.

In June 1934, a patent application was filed at the British Patent Office by the Normaton Filmgesellschaft of Berlin for a ‘Film-Taking Installation’ (GB439969, granted 18 December 1935). Normaton had been established by Arzén von Cserépy, a filmmaker of Hungarian origin who had produced a series of politically charged historical films during the 1920s and who has been discussed in the STUDIOTEC blog about unbuilt film studios German Film Studios of the Imagination.

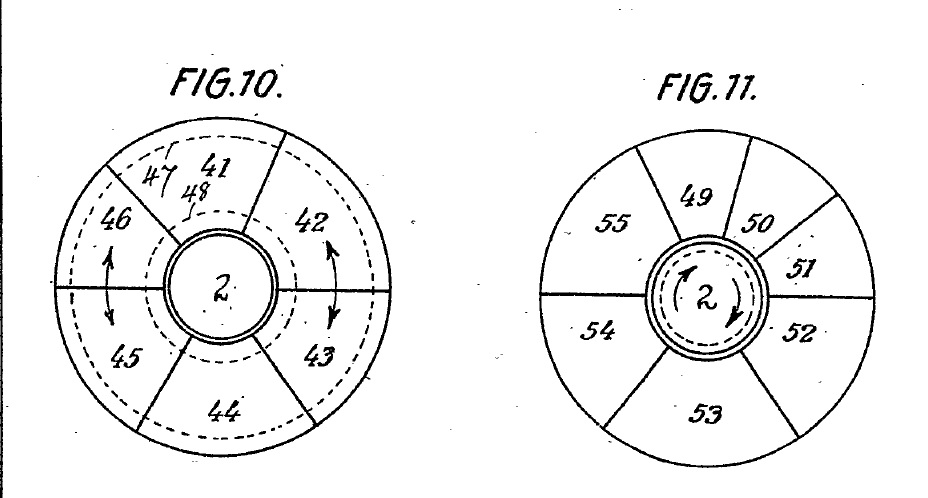

Cserépy /Normaton’s patent proposed a series of wheeled units that could be transported via rail and slotted together in the desired combination once they reached their destination. They would feature generic studio sets as well as lighting and sound units and their intention was to simplify studio processes by tidying up the cables and lighting equipment and reducing the labour and material costs of set building. The application describes:

a plurality of sets [that] are transportable on an endless rail track and the filming unit (2) is stationary and situated within said rail-track (figs. 10 and 11)

Which brings to mind a scene of the wagons being circled in a John Wayne Western…

The British patent refers to an earlier German priority, citing the date it was first registered in Germany (26 July 1933). In Germany, however, all trace of this earlier application seems to have vanished, and an online search only lists the British and Spanish applications. If this was a crime scene, the prime suspect was Ufa! Board minutes from 18 September 1934 indicate that the company played a part in the patent’s disappearance from the German record. Discussing Normaton’s proposal ‘concerning studio equipment, in particular the movement of the camera on rails’ they heard that ‘Normaton intends to levy a charge only on foreigners who film in German studios when using the processes’. The Ufa board agreed that:

an attempt shall be made to have the standardisation body grant a general licence free of charge to all German studio companies and film producers, including foreign studio customers, in view of the special benefit of the registered processes for the entire German film industry. In the event that this far-reaching right of joint use is rejected, the patent claims will be further challenged. It is considered expedient not to file the oppositions as Ufa but via a professional association. (BArch R 109-I/1029b).

Was ‘the far-reaching right of joint use’ rejected and did Ufa succeed in challenging the application, thereby excising it from the records? On 2 October 1934, the board agreed to file a counterclaim against the Normaton application and to encourage other production companies to do the same (BArch R 109-I/1029c).

A Spanish application was filed at the same time as the British one (‘Una instalación para impresionar films o películas’ ES134772A1, granted 16 August 1934), but that document is not available online. Regardless of what was happening with the German application, the British Patent Office approved the application and granted the Normaton patent on 18 December 1935. Whether Normaton’s system was ever considered a serious option by any European film studios is not recorded. Did the inventor envisage production companies buying and storing these units? Were they intended to be rented out and regularly transported across the national rail networks? Would such networks have even been in the position to transport these carriages? If Ufa was behind the disappearance of this patent, was it seriously concerned that Normaton’s model might prevail? There are more questions than answers here! The British patent is available to download in its entirety from Espacenet and its illustrations themselves are noteworthy.

References

Patents can be a rewarding resource for the film historian and many of the application documents are now digitised and can be accessed online. Those filed in Germany can be searched via the Deutsches Patent und Markenamt, as well as the European Patent Office website where applications filed in Britain, France and Italy might also be found.

Manfred Gill, Heinz Mustroph, ‘Filmfabrik Wolfen. Wiederaufbau und schleichender Niedergang’, Chemie in unserer Zeit, 49 (2015): 182-194.

Petr Szczepanik. Krieg der Patente. Die deutschen Elektrokonzerne und die tschechoslowakische Filmindustrie in den 1930er Jahren. In Zwischen Barrandov und Babelsberg. Deutsch-tschechische Filmbeziehungen im 20. Jahrhundert. München: Edition text+kritik, 2007. s. 43-56.