By Tim Bergfelder and Eleanor Halsall

Although STUDIOTEC’s focus is on the physical spaces that existed during the period 1930-60, a compelling question emerges about studios that were planned, but never, or only partially, realised. Work in the archives continues to reveal such proposals, which range from relatively modest plans that were briefly considered before disappearing from view to proposals that imagined a monumental, world-leading complex at Babelsberg.

Although these designs remained mostly on paper, they provide insights into the evolution of the film studio and how its future was being conceived as the medium of film production grew in maturity and complexity. Comparative work on the topic of unbuilt studios in Britain includes Richard Farmer’s article about proposals for ‘an English Hollywood’ in Esher in 1930 and Sarah Street’s article examining Helmut Junge’s 1944 Plan for Film Studios. Here we discuss a magnificent film city designed by architect Hans Poelzig; a studio intended for the exclusive use of Leni Riefenstahl; and a studio near Munich proposed for post-war Germany.

Hans Poelzig’s designs for a film city

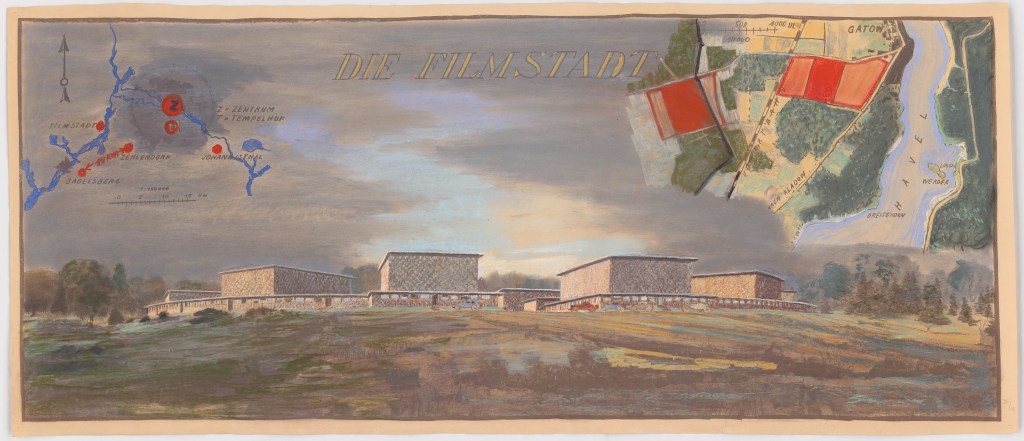

To the southwest of Berlin, close to Lake Glienicke and on the way to Potsdam, Arzén von Cserépy (1881-1958), the Hungarian owner of the Cserépy-Filmgesellschaft had acquired an area of 680,000 m2. In the latter months of 1930 he commissioned architect Hans Poelzig (1869-1936) to draw up plans for an extensive film production enterprise on this elevated site, and many of these drawings are digitally available from Berlin’s Technical University. Cserépy, a Hungarian filmmaker who had made the highly popular and nationalistic Fridericus Rex film cycle in the 1920s, later patented a process which might be described as off-the-peg mobile film sets, but that’s a story for another blog! In 1933 Cserépy founded the Normaton-Filmgesellschaft and building work began on the Glienicke site. This was halted soon afterwards, however, when he was forced to cede the land to the Luftwaffe which was building an airport at nearby Gatow.

Unfortunately, Poelzig’s idiosyncratic approach to studio design never saw the light of day. But his designs, which can be deduced from the sixty or so images available in the University’s archive, lead us to contemplate how their realisation might have altered Berlin’s film ecology. Might they have held a triangular balance with Babelsberg and Tempelhof, as hinted at in the image below? Or would they have intensified rivalry between production companies?

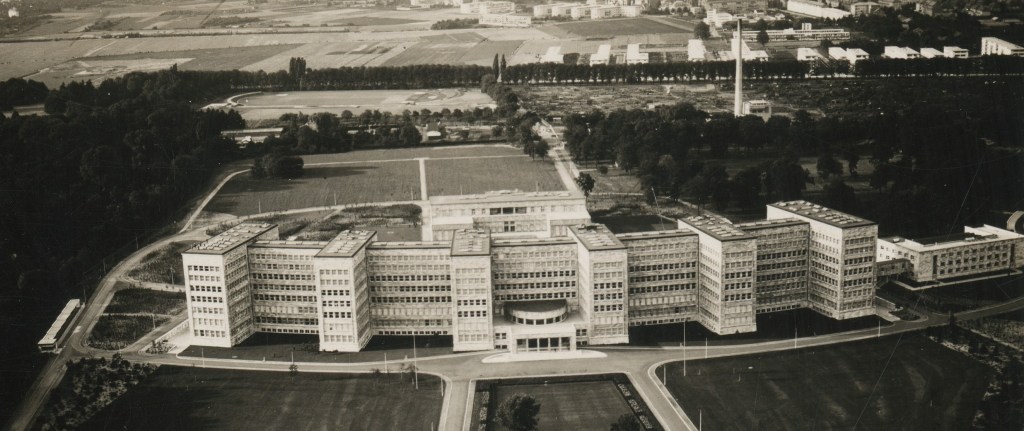

Poelzig was most prominently associated with expressionism and the New Sobriety movement. His designs included commercial buildings, office blocks, cinemas (such as Berlin’s celebrated Babylon cinema which is still in use as a cinema), and University buildings, combining functionalism with dramatic angles, curves, and edges. One of his most significant commissions was the IG Farben Haus in Frankfurt, built in 1929/30, which bears some resemblance to his plans for Cserépy. In the early 1920s Poelzig also worked as a production designer, most notably on Paul Wegener’s Jewish horror tale Der Golem (1920) as well as on Ernst Lubitsch’s Anna Boleyn (1920).

IG Farben Frankfurt

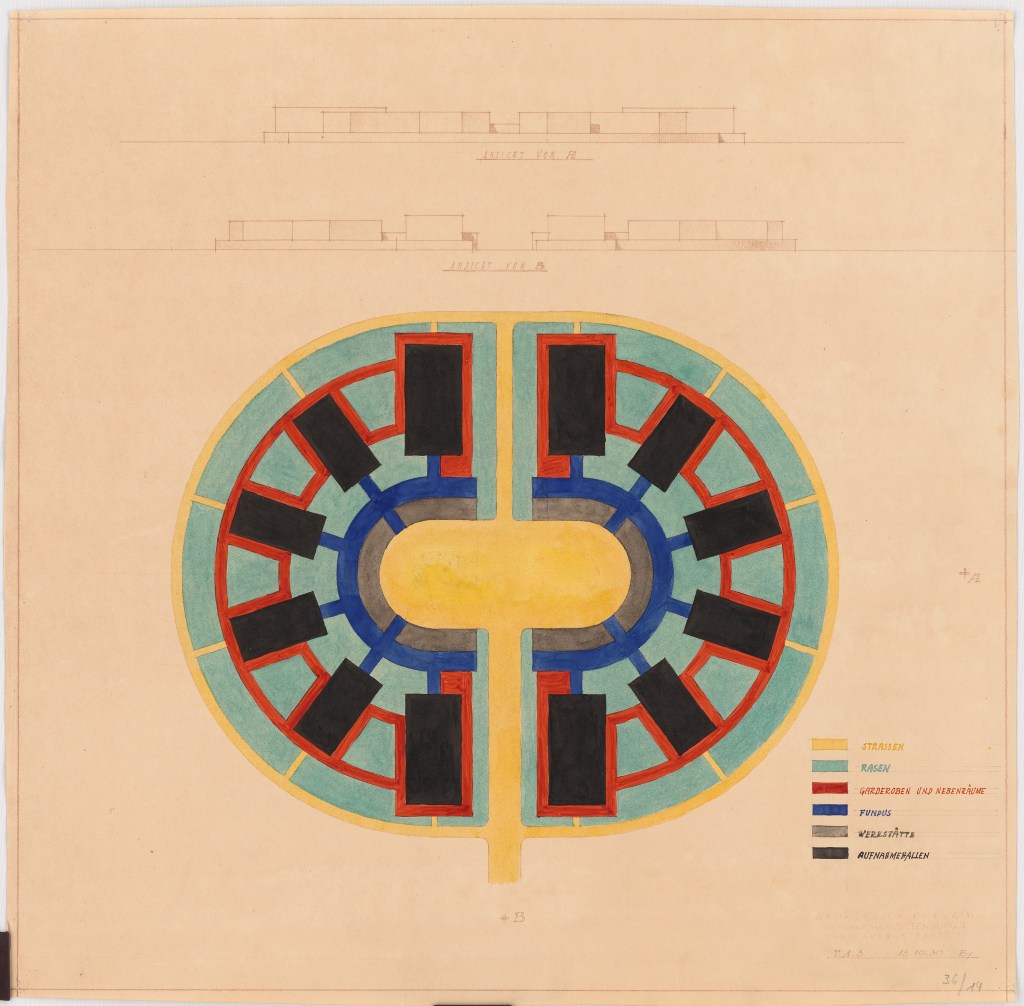

The surviving plans indicate a twelve-studio complex in a doughnut configuration, which echoed similar circular approaches to contemporary residential housing schemes, as in Bruno Taut’s famous ‘Horseshoe Estate’ (Hufeisensiedlung, 1925-33) in the Berlin district of Britz. Hufeisensiedlung Britz – Berlin.de

Poelzig’s plans envisaged encircling facilities for developing, editing and copying film prints and providing space for workshops, prop storage, dressing rooms and other activities related to film production. The plans featured twelve studios, four larger ones measuring 25 x 50 metres in length, and another eight studios measuring 20 x 40 metres. Was this plan too ambitious and expensive? A slightly later drawing presented a more rectangular design, with less studio space and a more conventional appearance.

Poelzig’s Rectangular Design for Gatow

Tantalisingly, we may never know which plan had been accepted once building work began…

A reward for Leni Riefenstahl?

Riefenstahl’s status as Hitler’s favoured director is well established. Less well known, however, was that the regime planned to provide her with a dedicated studio in Berlin-Dahlem, a project that lost impetus when war broke out in September 1939.

Dahlem map

A greenfield site of 22,500m2 that lay a little north of the Argentinische Allee was approved by Hitler for this purpose and Riefenstahl’s preferred architect, Dr Ernst Petersen, set about the designs. The favouritism of Riefenstahl was already controversial: her compulsive attention to detail resulted in her films running over budget and blocking vital resources of studio space urgently needed by other directors (Trimborn 2002: 282). That her production company had not been nationalised and remained a private concern even after the mass nationalisation of June 1941, further entrenched the asymmetric power struggle between Riefenstahl and her peers.

Petersen’s plans, held at the Bundesarchiv, discuss a main building, a copy facility, a studio and an auxiliary building which would contain garages and a porter’s lodge. The buildings were to be constructed with bricks, windows and doors to be edged with Roman travertine (limestone); all roofs were to be tiled with traditionally German reddish-brown Bieberschwanzziegel, see below.

The main building was to include photographic studios and workrooms, editing rooms, two projection rooms, a synchronisation room, several negative rooms, an exhibition room, a canteen and kitchen, a common room, and Riefenstahl’s private suite. Furnishings and fittings throughout the complex would be to a high standard, the exterior windows would be protected with shutters; Riefenstahl’s own windows would be protected with metal grating. Unfortunately for Riefenstahl, the project did not progress further. By the time the war ended, all opportunity for her private film studio was lost.

New beginnings?

The post war occupation significantly altered the landscape of film production with the forced decentralisation of the German industry in the western zones. Berlin was divided and the western zone of the city contained hardly any studio infrastructure except for the war-damaged Tempelhof complex; Babelsberg and Johannisthal now both lay in the east. Geiselgasteig in Munich’s south had remained relatively unscathed, however, the Americans now had control of that area and were reluctant to revive the German industry. Hamburg fell in the British zone and the focus settled on Hamburg as the West’s new film city. Over the next few years a number of new studios would emerge in West Berlin and Hamburg, and in more unlikely locations such as Wiesbaden, Göttingen, and rural Bendestorf. Other planned studios never saw the light of day however.

Gartenberg (Munich)

In the late 1940s, the press announced the prospect of Bavaria becoming the centre of film production in West Germany, and reported the plan for an ambitious new studio complex ‘Gartenberg’ in leafy Wolfratshausen in the Isar Valley, thirty-five km south-west of Munich in the vicinity of the scenic Lake Starnberg. The plan envisaged a complex divided into five distinct areas, with one large soundstage of 30 x 40 m with special sets for specialist shoots and documentary films, and another large studio with connections to a back lot for outdoor shoots, as well as an administration building, printing labs, editing labs, screening facilities, two hotels and apartment buildings for longer-term residents. Under the aegis of architect Hanns H. Kuhnert and with advice from veteran Bavarian producer Peter Ostermayr, the original founder of the Geiselgasteig studios, the project team hoped to utilise a former factory complex and predicted to finish the needed building works within ten months. Although the plan found initial approval from the Bavarian finance ministry, voices from nearby Geiselgasteig were more sceptical, arguing that the capacity provided by Geiselgasteig and the other existing West German studios made a further studio unnecessary. It appears that the funders of the Gartenberg plan were ultimately persuaded by this argument, and the plans were abandoned. A few years later, another ambitious plan for a new studio complex in rural Hesse near Darmstadt equally came to nothing.

References and acknowledgements

Architekturmuseum der Technischen Universität Berlin, Inv. Nr. 4956-4987 and HP036,001-036,028. Available online at Architekturmuseum der Technischen Universität Berlin (tu-berlin.de) accessed 7 November 2023.

Bayerische Wirtschaft, June 1949, p. 7.

BArch R 4606/2693, ‘Atelierbau für Leni Riefenstahl in Dahlem, Verlängerte Waltraudstraße, Hochsitz- und Holzungsweg‘ 1939-42.

BArch DR 2/8257, ‘DEFA Bauvorhaben’ 1946-47.

Bio-Filmographie Arzen von Cserépy (filmmuseum-potsdam.de) accessed 7 November 2023.

Editor: Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes, Widerstand und Verfolgung im Oberösterreich 1934-1945, Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, GmbH, 1982.

Farmer, Richard, ‘The English Hollywood that wasn’t: shadow history and Esher’s unbuilt film studios’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Taylor and Francis Online, 2022.

Filmstadt Gartenberg in Neue Zeitung, 18 June 1949.

Filme und ihre Zeit (newsletter) – Groß Glienicke als Drehort. Available online at https://www.filmschaffende-in-gross-glienicke.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Newsletter-5-September-2021.pdf accessed 7 November 2023.

Street, Sarah, ‘Designing the Ideal Film Studio in Britain’, Screen, vol. 62, no. 3, 2021, pp. 330-58.

Jürgen Trimborn, Riefenstahl, eine deutsche Karriere, Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag, 2002, pp. 281-285.

2 thoughts on “German Film Studios of the Imagination”