By Eleanor Halsall

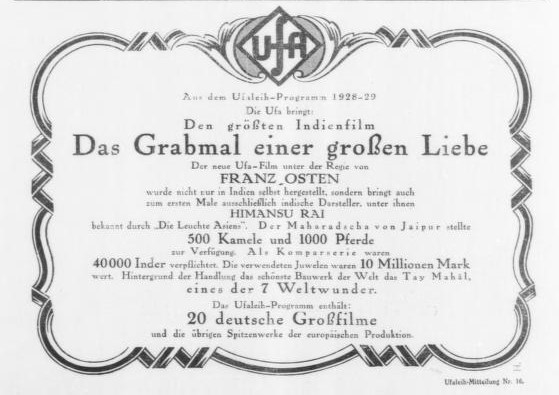

Film historiography is rich with tales of movies boasting casts of thousands, the hyperbole contributing to a film’s renown. Gandhi (Attenborough, 1982) is credited by the Guinness Book of Records as having had the largest ever crowd scenes involving 300,000 extras, a feat achieved long before computer generated imagery (CGI) altered the score. War and Peace (Bondarchuk, 1965) portrayed a battle using 12,000 real soldiers; an achievement previously surpassed by the Ufa propaganda film, Kolberg (Harlan, 1945) which made use of some 15-20,000 troops, their availability facilitated by a state of outright war. Das Weib des Pharao/The Pharaoh’s wife (Lubitsch, 1921) supposedly required 150,000 extras; with Kinematograph later commenting that ‘because such a large number of extras was not available in Germany, they had to make use of the unemployed’ (14 September 1927). This latter statement resonates with the precarity of the extra’s role: ‘Acting (as an extra) means earning money; having to feed a family; having to fight a continuous battle for an engagement for 10 marks a day; always being in the shadow of luck and not being noticed’ (Dortmunder Zeitung, 9 July 1937). In promotions (see below) for its silent film, Das Grabmal einer grossen Liebe/Shiraz (Osten, 1928), Ufa prided itself for the flock of 500 camels and 1,000 horses, 40,000 Indian extras, and the loan of priceless jewels from the Maharaja of Jaipur, in that order, a textual hierarchy locating the 40,000 humans somewhere between animal and mineral.

What was it like to be an extra in German film production during these mid-century decades? One of the more instructive films for this discussion is Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1926). Not only did Lang employ huge numbers of extras, but his treatment of this bedraggled, anonymous workforce might be described as negligent at best: ‘Lang’s tendency was to flatter the powerful, while picking on the weak and vulnerable, not only the crew, but the lowly extras’ (McGilligan, 118). Lang kept producer Erich Pommer busy with his demands for thousands of extras which included 4,000 bald men, 500 hungry children, and an army of naked males who were forced to act in the freezing winter conditions at the cavernous studio at Staaken, a former Zeppelin hanger in Berlin (119). At a time of mass unemployment and economic destitution, persuading people to participate was relatively straightforward because, in spite of the callous treatment they were subjected to on set, they were at least fed.

Brigitte Helm and extras

Lang was not the only director whose treatment of this transient workforce was controversial. Leni Riefenstahl’s production of Tiefland (1944/1953), a film that took more than four years to complete, included 100 Sintis who she personally selected from concentration camps; once filming was complete, they were despatched to Auschwitz where the majority were murdered (Tegel 2006). Several decades later, Werner Herzog ran into problems when he was pursued by allegations that Peruvian extras had been dragooned to appear in Fitzcarraldo (1982), a story about an individual who had been guilty of violence and abuse against locals at the beginning of the 20th century (Filmkritik 1979).

Brigitte Helm and extras

Visual metaphors in Metropolis illustrate the subaltern status of the film extra. In one, the levers wielded by Brigitte Helm contrast with the arms of the children in stretched upwards in apparent supplication. In another, extras appear crushed against one another, sharing Gustav Fröhlich’s panic.

Extras in Metropolis

The extra subsisted on the fringes of film production, a position of extreme precarity, low wages and absence of self-determinism. It was a role requiring endless patience and a high degree of stamina. Far removed from the speaking parts which commanded attention on the screen, in terms of agency an extra was much closer to the props and requisites that provided the background scenery. Dedicated entrances at large studios such as Babelsberg and Geiselgasteig, as well as separate canteens and changing rooms, emphasised their physical separation from the rest of the cast and crew. Extras received no accreditation and had no dialogue, yet their presence was essential as what Picturegoer described as ‘atmosphere representatives’ (23 January 1932). Chosen by characteristics such as gender, height, ethnicity and age, these were the people who jostled in crowd scenes, created the Geräuschkulisse – the background buzz – in restaurants and theatres, and milled about on train platforms as bodies for the lead actors to push through. Just as the carpenter ordered spans of wood, so the production team would source the appropriate extras. Unlike planks of wood, however, extras had to be managed, fed, paid and, in an ideal world, looked after properly.

In German speaking countries the role of extra is usually described as a Komparse viz. Komparserie (the cast of extras) a term which Duden informs has its origins in the Italian term comparsa. Statist was more commonly applied for work in theatres, but also appeared in articles about film. The Kleindarsteller (a bit part actor) was generally named in the internal cast list, yet at other times was described as a film extra, an ambiguity reinforced by regular term switching in internal studio documentation. The Körperdouble (the stunt or body double) and the Lichtdouble (the light double or stand in), terms welded together from two languages, are used to replace the main actors either where the latter’s safety or dignity is concerned or when the photographer needs a body to check lighting and focusing.

Who worked as an extra? Film Magazin described the Komparserie as consisting mostly of former artistes and stage workers (24 March 1929); and Slide (2012) dedicates a chapter to Hollywood’s erstwhile silent stars who were reduced to working as extras. This notion of the extra as an elite individual who has fallen on hard times even features in The Last Command (Sternberg, 1928) when Sergius Alexander, a former grand duke played by Emil Jannings, is reduced to hustling with others to get occasional work as an extra in Hollywood. In an ironic twist, Jannings received the first ever Academy Award for acting…as an extra!

When names of film extras emerge, they usually do so obliquely, typically through a news item about an accident on set or a reference in meeting minutes. In July 1931 a dancer waiting to perform on Der Kongreß tanzt/Congress Dances(Charell) at Babelsberg, was fatally injured when a carbon ember landed on her dress, setting it alight (Mein Film, 1931). Lili Ernesto’s demise did not even warrant a mention in the board minutes. The accidental death of another female extra in March 1944 occurred during production of Wiener Mädeln / Viennese Maidens (Forst, 1945/1949) and resulted in a half day suspension of filming. ‘Pilandrovà – Komparsin’ is the only indication of the person whose demise resulted in a claim for compensation – RM 10,996.90 – to the benefit of the production company, Wien Film (R 109-III/58). In August 1933 Ufa’s board approved funding for a prosthetic leg for one Mr Jilenkoff. Referred to as an ‘incidental participant’ on Der weisse Teufel / The White Devil (Wolkoff, 1930), Jilenkoff’s actual role and the cause of his amputation is not known (R 109-I/1029a).

Slide (2012) describes how Hollywood extras were paid according to how authentically they fitted the type. Wearing their own clothes, especially formal dress, attracted slightly higher payments which could make a significant difference if work continued for several days. A similar system operated in Germany. In 1942, for example, an extra required to be an incidental part of a crowd scene (classed as more than 75 people) took home RM10 per day. If the extra was a professional person, however, this increased to RM15. An actor wearing ordinary day clothes could claim RM20; donning a historical costume or a better-quality outfit attracted RM25, but an actor in a ball gown or top hat and tails might earn RM35. Speaking parts were remunerated at RM40 and singing at RM30. Bringing personal equipment attracted supplements, such as RM5 for a set of skis or RM3 for opera glasses. Skills in another language used on set were more richly rewarded with a supplement of RM50 (R109-I/9a). The following table shows how some of these payments increased over the period 1935-1949:

| Payments for film extras and stand ins | 1935 | 1942 | 1949 |

| Participation in crowd scenes (75 or more) | RM10 | RM15 | RM20 |

| Everyday street clothes | RM15 | RM20 | RM25 |

| Smarter street clothes or historical costume | RM17 | RM25 | RM30 |

| Frock coat, ball gown or similar | RM25 | RM35 | RM35 |

| Rider, swimmer, skier, sailor and similar sports activities | RM25 | RM35 | RM35 |

| Speech, mime or song | RM30 | RM40 | RM40 |

| Supplements for: – | |||

| Standing in as a light double | 0 | RM10 | RM10 |

| Bringing opera glasses, tennis rackets, small suitcases | RM3 | RM3 | RM3 |

Data from DEFA report on pay and conditions for extras, DR 117 33224, December 1949

In addition to these rates, provision was made to cover delays, overtime and cancellation due to poor weather conditions, when government approved payments could be made. Although some conditions gradually improved for extras, after 1933 the barriers to entry became increasingly restrictive. Building on earlier bureaucracy which oversaw the employment of film extras through the Arbeitsamt (Die Bastion, 19 April 1936), Bavaria Filmkunst appointed Dr Alexander Gessner in February 1939. His specific role was to manage actors and extras, defined as those commanding a daily rate of less than RM 200, and to liaise with directors and producers to ensure that only extras with the correct paperwork were employed on films (R 109-I/2357). This was symbolic of the tight control that the regime in Berlin exercised over the German film industry, a situation further entrenched when the Ministry of Propaganda created a dedicated agency for film extras – the Einsatzstelle für Filmkleindarsteller – in September 1941; the purpose of which was to provide a contingent of officially sanctioned extras, and provide them with regular contracts and income (R 109-I/1034b).

Around the world, and in spite of the use of CGI, the film extra continues to be in demand. Perhaps this comment, from post war Austria explains the attraction? ‘The work of the people employed as extras is hard and without luxury. In the heat of the studio they often wait for hours in winter clothes, in winter outdoor scenes in summer dresses and light suits … this is how the nameless actors contribute to the success of the film. In spite of everything, they love their occupation, and the days on set … not only mean work and earnings for them, but also a certain satisfaction by participating in the cultural work of the film’ (Österreichische Zeitung, 10 July 1948).

References

Anon, ‘Babelsberger Bilderbogen’; die bekannten Gesichter, Jeversisches Wochenblatt, 27 February 1931.

Anon, ‘Es ist nicht alles Gold… Die soziale Lage der Filmkomparserie’, Die Bastion, 19 April 1936, 2.

Anon, ‘Figuren im Hintergrund’, Film Magazin, 24 March 1929.

Anon, ‘Tragischer Unfall in einem Filmatelier’, Mein Film, 295, 7.

Anthony Slide, Hollywood Unknowns: a History of Extras, Bit Players, and Stand-Ins, University Press of Mississippi, 2012.

BArch DR 117/25928, ‘Die letzte Nacht’.

BArch DR 117/33224, ‘DEFA Zentral Fundus’.

BArch R 109-I/9a, ‘Berlin Film GmbH’.

BArch R 109-I/1029a, 30 August 1933. Ufa Board Minutes.

BArch R 109-I/1034b, PK 1469, 1 Oct 1941. Ufa Board Minutes.

BArch R 109-II/40, ‘Tobis Filmkunst GmbH’.

BArch R 109-III/58, ‘Schadensrechnung’, 22 July 1944.

Berndt Böhle, ‘Und einmal kommt doch das Glück…’, Dortmunder Zeitung, 9 July 1937, 9.

Carl-Erdmann Schönfeld, ‘Franz Osten’s The Light of Asia (1926): A German-Indian Film of Prince Buddha’. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 15:44 (1995): 555–61.

Das Herkunftswörterbuch, Duden, 2020.

Filmkritik – n273 September 1979, 442-443.

Friedrich v. Zglinicki, Eduard P. Andrés, Wie komme ich zum Film?

Heinz Udo Brachvogel, Kinematogaph, Nr. 1072, 14 Sep 1927, 13.

L. F., ‘Das Heer der Namenlosen des Films’, Österreichische Zeitung, 10 July 1948, 6.

Margaret Chute, ‘That Little Extra’, Picturegoer, v.1 n.35, 23 January 1932.

Patrick McGilligan, ‘Fritz Lang, the nature of the beast, Faber and Faber, 1997.

Susan Tegel, ‘Leni Riefenstahl’s Gypsy Question Revisited: The Gypsy Extras in Tiefland’, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 26:1 (2006), 21-43.