By Steven Roberts

The ‘Film Studios’ conference provided a forum for international research, looking beyond traditional geographical, historical, and methodological boundaries of studio research in keeping with the comparative STUDIOTEC project, which hosted the event in Bristol between 5-7 June 2023. Over three full days, the ideas of invited speakers flowed freely and were received by an attentive audience, who then put forward insightful questions during each session. Postgraduate students, early career and established researchers all participated in the production of knowledge. In addition, one of STUDIOTEC’s exciting outputs, a Virtual Reality experience, transported delegates to historic European studios.

Given that creative spaces were the conference theme, let’s begin with the carefully chosen venue. The Watershed is a media production and film exhibition centre that has become a cultural landmark for the city and nationally, also attracting scholarship (Presence 2019). Conference delegates walked through the cinema lobby to be received each morning in the café, with generous views over the Bristol harbourside. The ample glass frontage connected internal and external space, reminding me of the distinctive locations in which artistic hubs like the Watershed can be found. Presentations themselves were delivered in the ‘Waterside’ rooms, just next to the site’s Pervasive Media Studio. The place of studios proved to be a strong theme, with research spanning Italy, India, Britain, Ireland, the USA, China, Germany, Czechia, Japan, Nigeria, France, Poland, South Korea, Romania, the United Arab Emirates, Australia, Chile, Argentina, Thailand, Saudi Arabia, and Singapore.

The ‘film studios in twentieth-century China’ panel take questions

Studios’ interconnectedness with their locality and nation was emphasised in the first keynote address, given by Noa Steimatsky, whose paper (‘Displaced in Cinecittà: Historiographic itineraries’) was layered with historical and poetic allusions to Italy’s past. ‘Walled and gated, Cinecittà is a circumscribed place’ in a physical sense, but, argued Steimatsky, alternative histories can help when ‘locating the studio in fascist Rome’, which is one of its key contexts.

Noa Steimatsky: ‘Displaced in Cinecittà: Historiographic itineraries’

Steimatsky’s paper mapped realised examples of architectural display and fascist propaganda onto the city, while also recalling an envisioned utopian ‘media industrial’ or ‘cinematographic zone’ (with reference to archival planning documents of the period). In this urban project, there was a key tension between the shapeshifting nature of studios and the fixed promises and projections of the regime. However, this fascinating paper went on to discuss the periodic coalescence of creative and political imperatives as Cinecittà transformed into a POW camp, highlighting the studios’ material correspondence to the classical military castra. Evidence of the studios’ alternating appropriation by fascism and then British intelligence significantly expanded on published work, including Steimatsky’s book chapter for In the Studio (2020), edited by the second keynote speaker, Brian R. Jacobson (please read to the end of the blog post to learn more about this last paper.)

It was exciting to see speakers variously respond to the themes of studio ‘histories, evolution, innovation, futures’ indicated in the conference subtitle. Panels such as ‘British studios before 1930’, ‘Film studios in twentieth-century China’, and ‘Excavating studio histories’ had a historical and historiographic focus, in using sources that tracked evolving studios from the silent, early sound and post-war eras of global cinema. Historical crisis and political change also proved to be a factor for studios’ evolution in certain panels, such as ‘Studios and filmmaking after war and partition’ and ‘film studios in state-socialist Poland’, respectively, which chimed with issues discussed in Steimatsky’s opening keynote.

STUDIOTEC VR: step into cinema (and the studios behind it)

Tuesday afternoon’s plenary session on Virtual Reality punctuated proceedings with the welcome opportunity to come together and gather our thoughts on the role of technology in contemporary studio studies. Amy Stone gave a precise overview of ‘STUDIOTEC VR’, but which delegates could also sign-up to experience individually, and in 360-degree virtual space, by wearing a headset under Stone’s guidance in the breakout space. The session considered the application of interactive design and user experience data in developing and refining the immersive tours of British, Italian, German and French studios. Researchers on the STUDIOTEC team had fed into the design process, so that appropriate modelling and educational reuse of primary sources could enhance the product. Lively discussion followed between conference delegates and the wider project team, touching on the opportunities of adaptability, standardisation, and aesthetics in virtual reality for better informing us about film studios in the not-too-distant future, and as the tech industry develops.

Innovative filmmaking connected to studios was explored in quite a few papers, including the context of ‘Virtual filmmaking’ that fittingly preceded Stone’s plenary address. Panels such as ‘contemporary animation studios’ and ‘animation studios’ explored the symbolic and material qualities of a multi-faceted technique, and the different environments in which this has flourished. The reliance on specific technical knowledge in the production workforce was also highlighted in panels such as ‘British studios’ (on construction, costumes, and staging techniques) and two diverse panels on ‘Studio working life and practices’. Although the field has sometimes usefully focused on architectural and technological aspects in isolation, other research reminds us that studios can belong to broader networks that include large communities of people. In this same vein, panels on ‘transnational studios and filmmaking’ and (yes indeed!) ‘beyond the studio’ reflected on the inter-cultural and social contexts of material infrastructures.

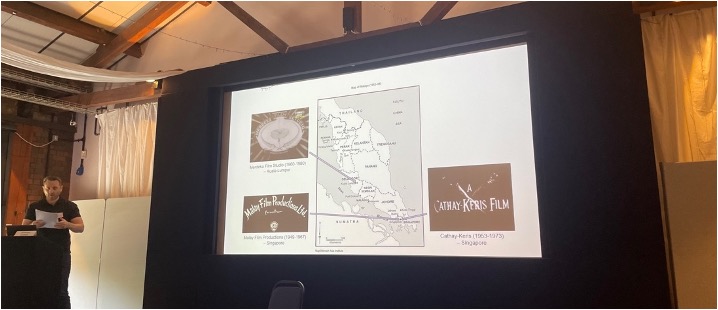

Jonathan Driskell: ‘Striking glamour: Studios and stardom in the “golden age” of Malay cinema’

The second keynote was given by Jacobson and was titled: ‘The studio of extractions and resource integration’. It embraced the revisionist thinking and even specific questions raised by previous papers, such as finding a place for film analysis in studio studies, or how historical examples can be brought into relation with current practices around sustainability. Jacobson began by acknowledging contributions to the field by Steimatsky, Sarah Street, Thomas Schatz and others, particularly as to how studios provide a ‘motor’ for various types of historical research. Revisiting the earlier approach to ‘filmless film studies’ which partly characterised the materialist monograph Studios Before the System (2015), the paper considered how both studios and their products embody the material world which industry ‘manages, uses and manipulates’.

The second keynote was delivered by Brian R. Jacobson

Echoing the taxonomy from his forthcoming book, Jacobson outlined the early cinema of extractions which developed into a cinema of resource integration, yoked to a resource-dependent economy. There followed a detailed analysis which aimed to ‘collide textual and material forms’, using case studies drawn from silent Hollywood cinema: The Lonedale Operator (D.W. Griffith, 1911) and Sunshine Molly (Lois Weber, 1915). Although the films relate to the mining and oil (extraction) industries, Jacobson noted that this was also for illustrative purposes, and that a range of examples resonating with the world’s resources could bridge ‘textual form, form of content, and the material conditions of production’. Alongside its open appreciation for canonical silent films and responses to them (e.g., Tom Gunning), the keynote address was informed by the later research of Caroline Levine, Lee Grieveson, and Jennifer Peterson. The total effect was one of looking backwards in time through a contemporary lens, with the films now appearing like a warning sign for our future. The methodology led to rich discussion during audience questions, considering the focus, affordances, and political role of analysis, and related terminology such as ‘indexicality’ and the ‘cinema of attractions’. When all was said and done, we were reluctant to call ‘cut!’ on the conference’s closing scene. Doubtless, the conversation around studios will continue.