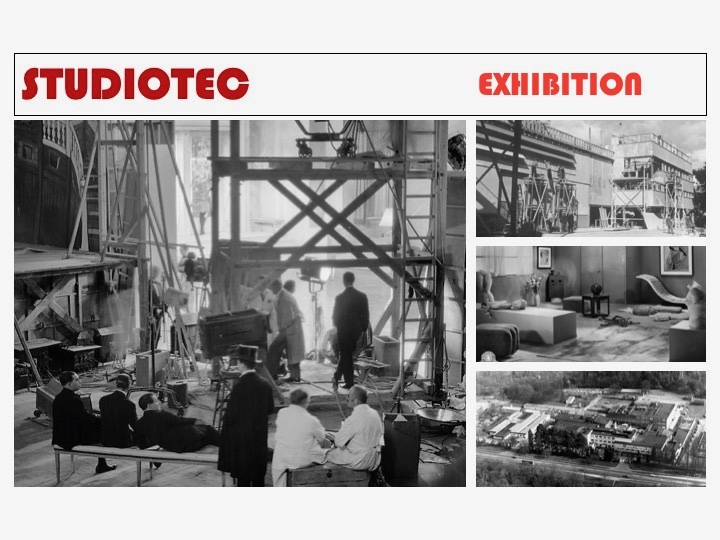

As well as making iconic films, studios in Britain, France, Germany, and Italy generated many diverse materials we have come across in our research. These illustrate the ways in which studios sought to attract public attention, celebrating their ingenuity, expertise, and place in regional and national contexts. This exhibit showcases objects and ephemera chosen primarily for their visual interest. These carefully chosen gems relate to advertising cultures of novelty, including logos and letterheads, postcards and trade cards, celebrations of technologies and techniques, and other fascinating curios the STUDIOTEC team have encountered.

Advertising the studios

Advertising was key to communicating the studios’ corporate identities, as well as locating them visually within the popular imagination.

Postcard of Pisorno film studio in Tirrenia, Tuscany. Photogapher and date unknown.

Pisorno was the first Italian film studio purposedly built for sound. This modern studio was located in Tirrenia, a seaside town founded in 1932, and derived its name from a combination of Pisa and Livorno, the two cities in its vicinity. The studio was within walking distance of Tirrenia’s sandy beach and surrounded by Mediterranean woodland. The attractive climate, coupled with the region’s rich architectural heritage, presented ideal conditions for filming in the studio’s backlot and on location for most of the year.

Renamed Cosmopolitan after Carlo Ponti and Maleno Malenotti’s controversial acquisition in the 1950s, the studio contributed to enhance the touristic appeal of the area at home and abroad until it closed in the early 1970s.

Publicity for Tirrenia studios, Variety, 26 April 1961, pp. 74-75. Notice the emphasis on its ‘most varied and colourful location’.

Stamps are official materials issued by a public office and in a similar way to banknotes and coins carry with them cultural and political symbols that are shared and valued by the society who uses them.

Italian postage stamp issued on 28th April 2007 for Cinecittà’s 70th anniversary. Printed by the State Mint and Polygraphic Institute.

Celebrating Cinecittà’s long-lasting legacy, the stamp brings together some rhetorical elements that are in various ways associated with the modern myth of Cinecittà.

The studios’ main entrance, located on the via Tuscolana in Rome, features prominently on the stamp, stretching across the entire length of the frame. Immortalised in several media from a similar street-level, obliquely angled perspective, this guarded liminal space has over the years reinforced the studios’ (and metonymically, the film industry’s) prestige and exclusivity.

The design chosen for the stamp juxtaposes another, more controversial, symbol historically engrained in the life of the studios. A middle-aged man emerges from the left-hand side of the frame, who uncannily resembles Benito Mussolini, the Fascist dictator whose government supported the construction of this large filmmaking complex to steer its activities for propaganda purposes.

Mussolini: photographer and date unknown.

This image appears to be the direct source for the figure outlined in the stamp. In the latter, however, Mussolini’s military fez hat has been replaced with a fedora type. The dictator’s infamous arm pose has also been modified to portray him handling a motion picture camera while also looking through its viewfinder. This reinterpretation neutralises Cinecittà’s early entanglement in politics while memorialising the role that Mussolini, not as the leader of Fascism but as a lay man, had in their genesis. This mythmaking operation remediates historical press records which extensively portray Mussolini as wearing military attire when he visited the studios. It also points to Italy’s uncomfortable relationship with that past.

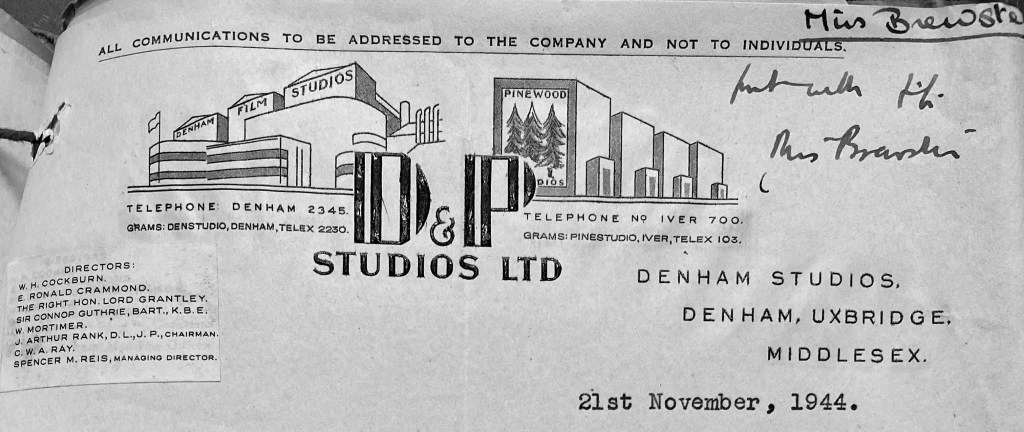

Logos and letterheads

Studios were corporate enterprises as well as centres of production and innovation. These documents illustrate some of the logos and letterheads generated in British studios.

Source: The National Archives: BT 64/95.

In 1939 Denham and Pinewood studios were merged for the purposes of corporate rationalization and management since they were both controlled by the Rank Organisation. D&P Studios Ltd was formed for this purpose and the company’s letterhead reflected the two studios’ logos.

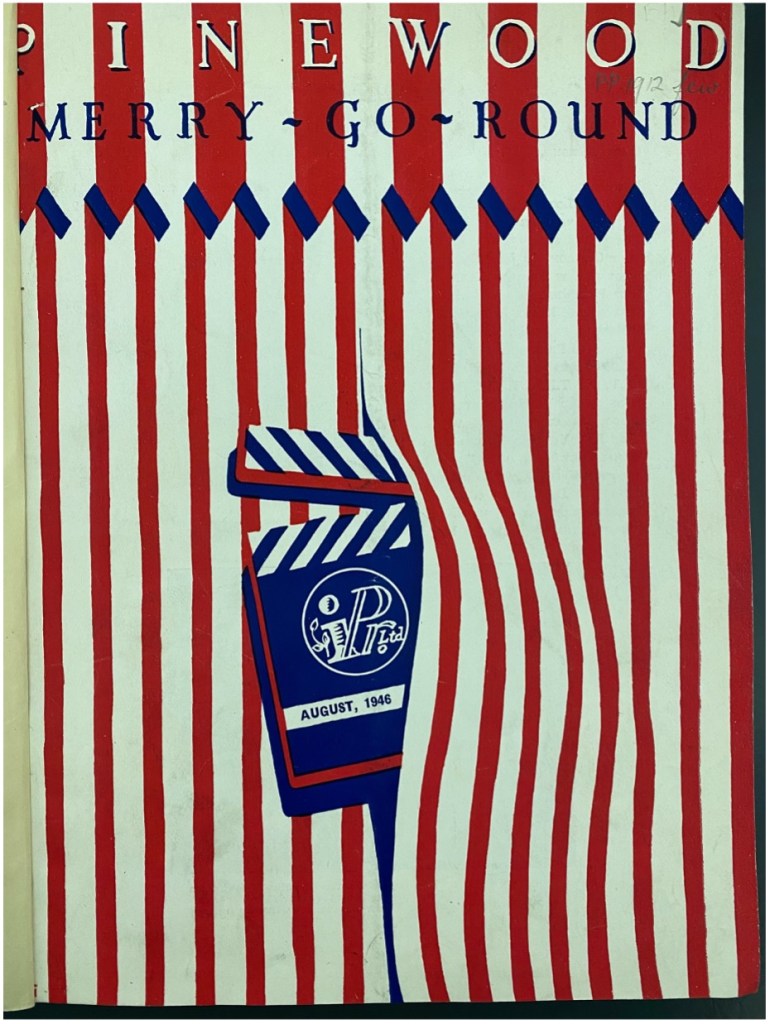

The Pinewood Merry-Go-Round was published monthly from August 1946 to December 1947 by Independent Producers, the holding company established by J. Arthur Rank in 1942 to finance and manage independent production companies.

Cover Pinewood Merry-Go-Round.

As a rare example of a surviving in-house publication produced by employees at Pinewood, the Pinewood Merry-Go-Round provides a rare glimpse into how studio employees bonded through sports and social clubs, musical and film groups, organising a Christmas pantomime, putting on art exhibitions, writing short stories, sharing studio gossip, and reporting issues of concern such as transport to work and long working hours. It was a high-quality publication produced at a time of severe paper shortages and post-war austerity.

Celebrating technologies

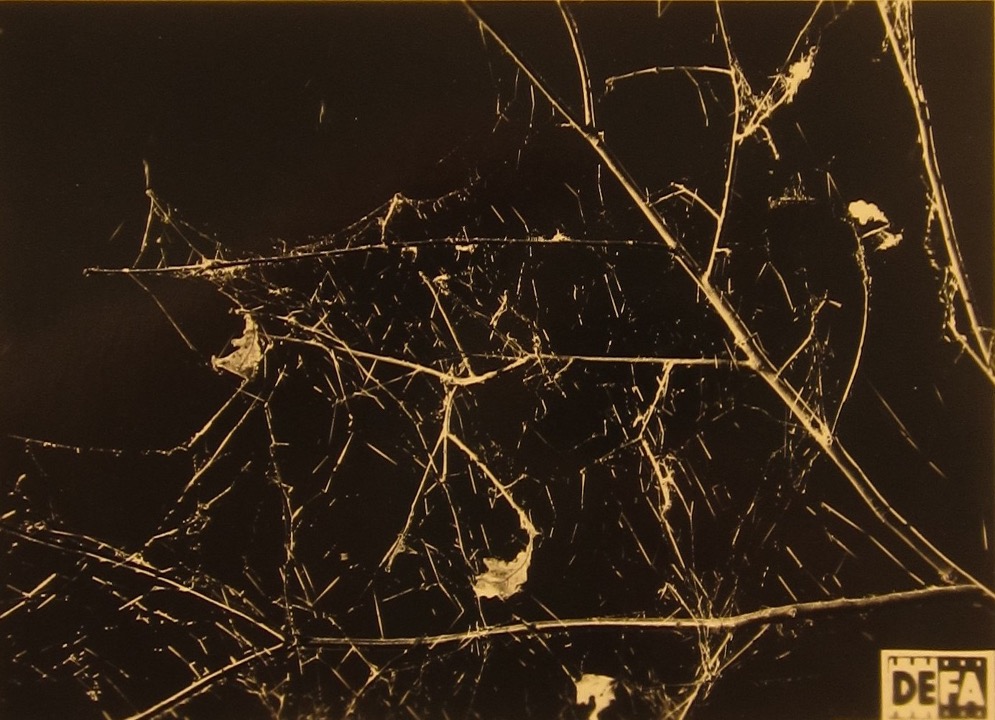

While many studio technologies such as cameras and lights were well-known, other inventions were more obscure. In Germany, DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft) produced a guide on how to make a spider web.

Arachnoids not being one of the more easily domesticated life forms that can be trained to weave webs on set (although this idea raises an interesting mental image!), filmmakers needed technical help to create a similar effect. Marvelling at the square kilometre of spider webs that were produced for one Hollywood production – The Egg and I (Erskine, 1947) – Mein Film commented that earlier versions – made from spun sugar – were now being produced using a secret method devised, most likely, by American set designer Russell A. Gausman.

One of a series of DEFA’s special effects guides from 1955 describes the studio’s own creation of artificial spider webs. It uses a tabletop fan with 220 V alternating current and a container for the spinning solution which is attached to the axis of the fan:

The above container consists of two copper sheet trays which can be pressed together firmly along their flat rims and secured using a knurled nut that can be turned by hand. Two nozzle-like etchings in each of the flat rims enable the spinning solution to be ejected, forming a fine thread. The fan drives the spinning threads forwards and, by moving the device accordingly, they can be sprayed directly onto the decoration to produce these images:

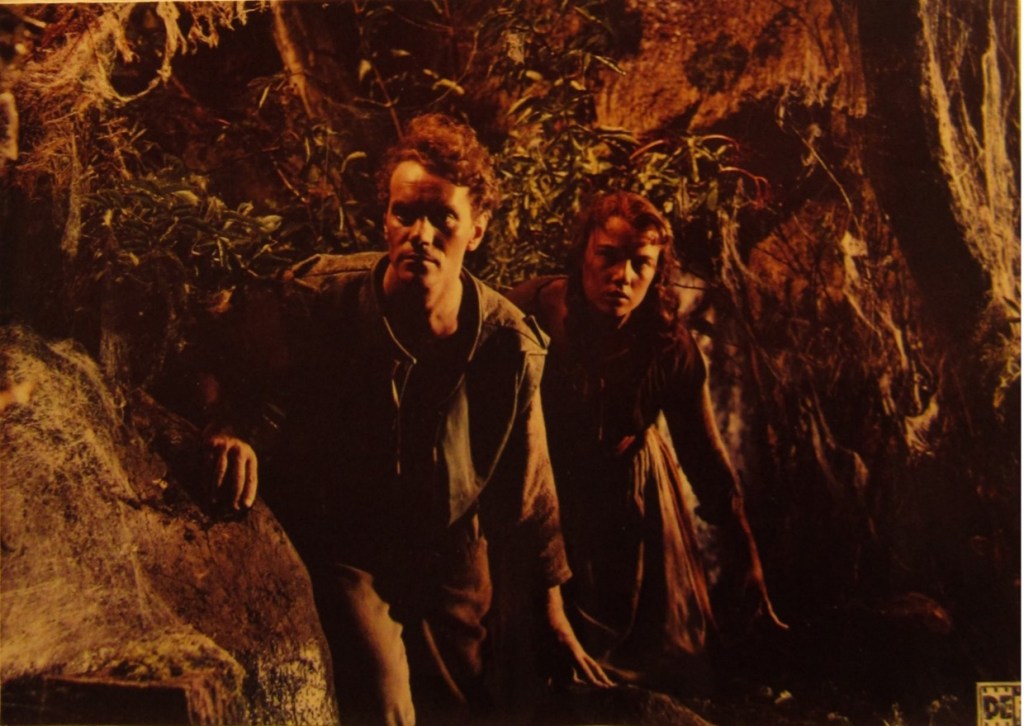

… and visible in this spidery scene from Der Teufel von Mühlenberg (Ballmann, 1955).

Earlier versions used a special rubber solution (not described) for the spinning solution, but by 1955 DEFA was using a spray agent (AV 503 H) supplied by the Agfa Wolfen film factory and usually used to spray walls in the Johannisthal studio. The spider webs are described as quick-drying and easy to remove because they rapidly lose their adhesiveness. Source: All images are from BArch DR 117/23632, Der Einsatz von Spinnweben bei Filmaufnahmen held at the Bundesarchiv at Lichterfelde, Berlin. ‘Spinnweben auf Bestellung!’, Mein Film, 26 September 1947, 1.

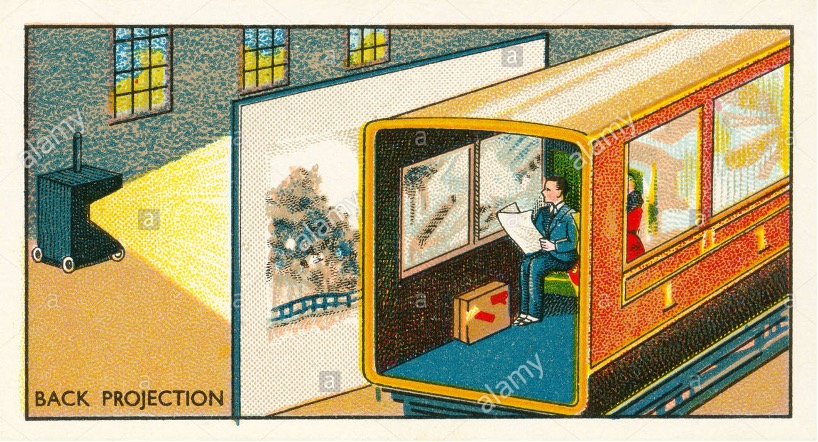

Studios specialized in the creation of many effects. One of the most distinctive was back projection which enabled footage shot previously in a location outside the studio to be projected in the studio with actors performing in front of the screen. This was filmed to create the illusion that the actors had been on location. The process saved production companies considerable costs that would have been spent sending an entire unit on location, and scenes shot purely for the purposes of back projection could be re-used as generic background in different films. The technique was explained in one of the cards in a set of promotional cigarette cards made in 1934 in Britain by B. Morris and Sons which explained how films were made.

Back projection cigarette card. Source: Alamy Stock Images C4AMF1.

Below is an image of a scene featuring a back projection set up in the studio. The film in which it featured was The Woman’s Angle (Leslie Arliss, 1952).

Source: The Cinema Studio, supplement to Today’s Cinema, August 1951, p. 27.

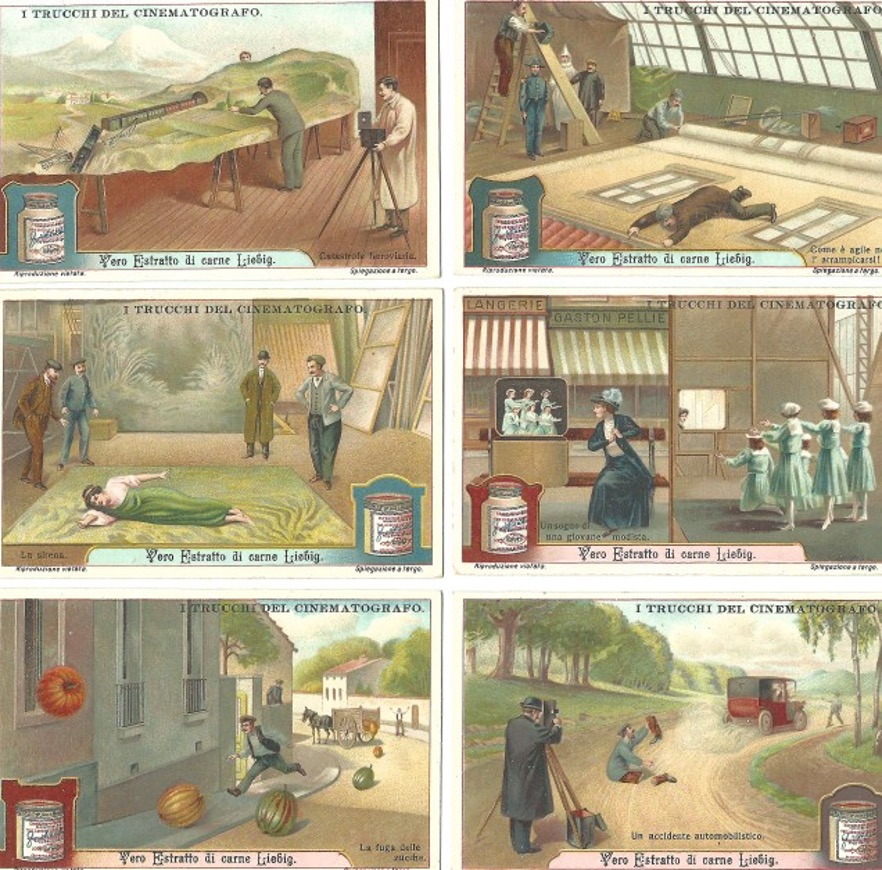

In Italy, the Liebig company’s collectible trade cards circulated in several European languages between 1872 and 1975. Even though the company produced soluble meat extract, their estimated 1,866 series of advertising cards covered an extremely heterogeneous range of topics. Liebig’s cinema series was released in Italy in 1913, the same year as the popular sword and sandal epics Quo Vadis and The Last Days of Pompeii.

Source: I trucchi del cinematografo, Liebig’s trade cards (series no. 1070, 1913) (chromolithograph on print, each card measuring 7x11cm).

Playing with film audiences’ fascination with spectacular visual effects, this series explains in simple terms how ‘film tricks’ were made inside the stages or on location. Similarly to the cigarette cards popular in Britain and Germany, each card had a detailed colour illustration on one side; on the other, the explanation of how the creative effect was achieved followed a short description of how best to use the Liebig company’s meat extract in a recipe!

Of note: the representation of (gendered) work in ‘glass and steel’ stages, revealing the use of flat, painted backdrops as scenarios, small box cameras on wooden tripods, and reliance on natural lighting. The introduction of sound and colour technologies would revolutionise film studio environments and practices.

A home-made air-cooling system

Excessive heat on the sets was one of the many discomforts complained about by studio employees. With the advent of sound film, arc lights were replaced by incandescent lamps which emitted more heat. Combined with the need to insulate shooting areas from outside noise, the air in film studios of the 1930s was often stifling and unbreathable. In hot summers this became worse since doors could not be opened to cool down the spaces, as was the practice in winter.

During the summer of 1941, on the set of La Prière aux étoiles, directed by Marcel Pagnol in the Marseille studios, the technical crews decided to cobble together a homemade air conditioner. A dozen blocks of ice were placed on a shelving unit, then a fan was placed behind the unit to blow cool, moist air onto the set. The melted ice was collected in a bucket and reused for other purposes. The caption to the image (published in Pagnol’s magazine Les Cahiers du film) states that 500kg of ice was consumed every day!

Les Cahiers du film, n°14, 1st September 1941, p.10.

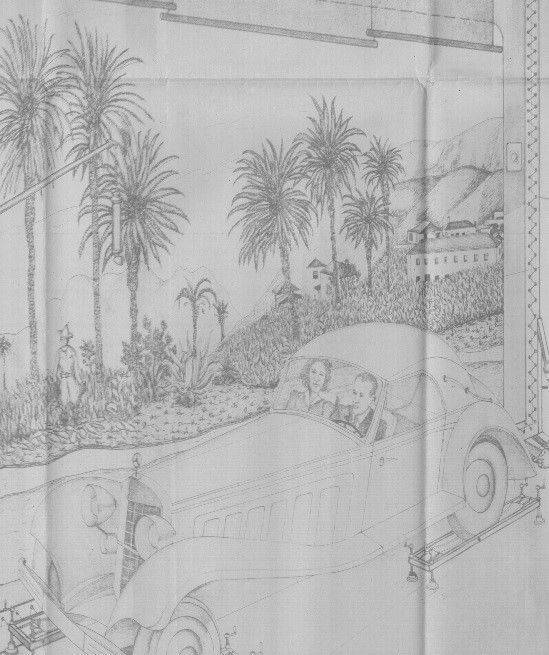

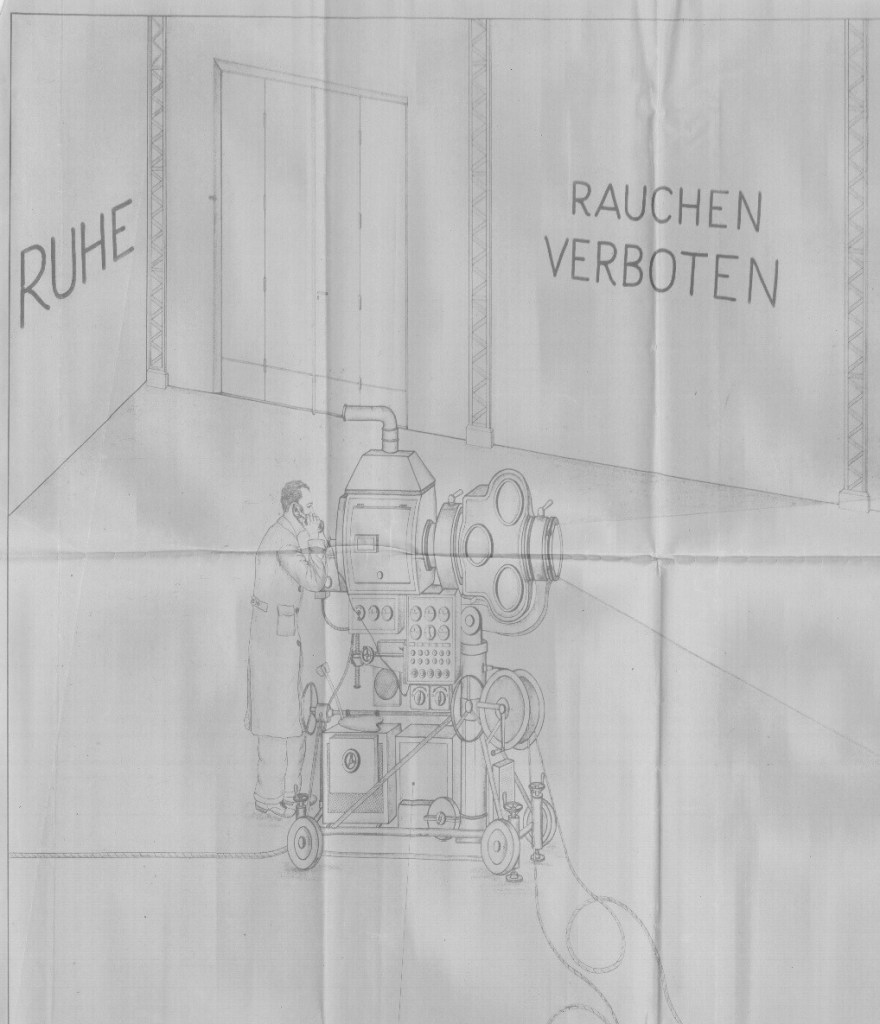

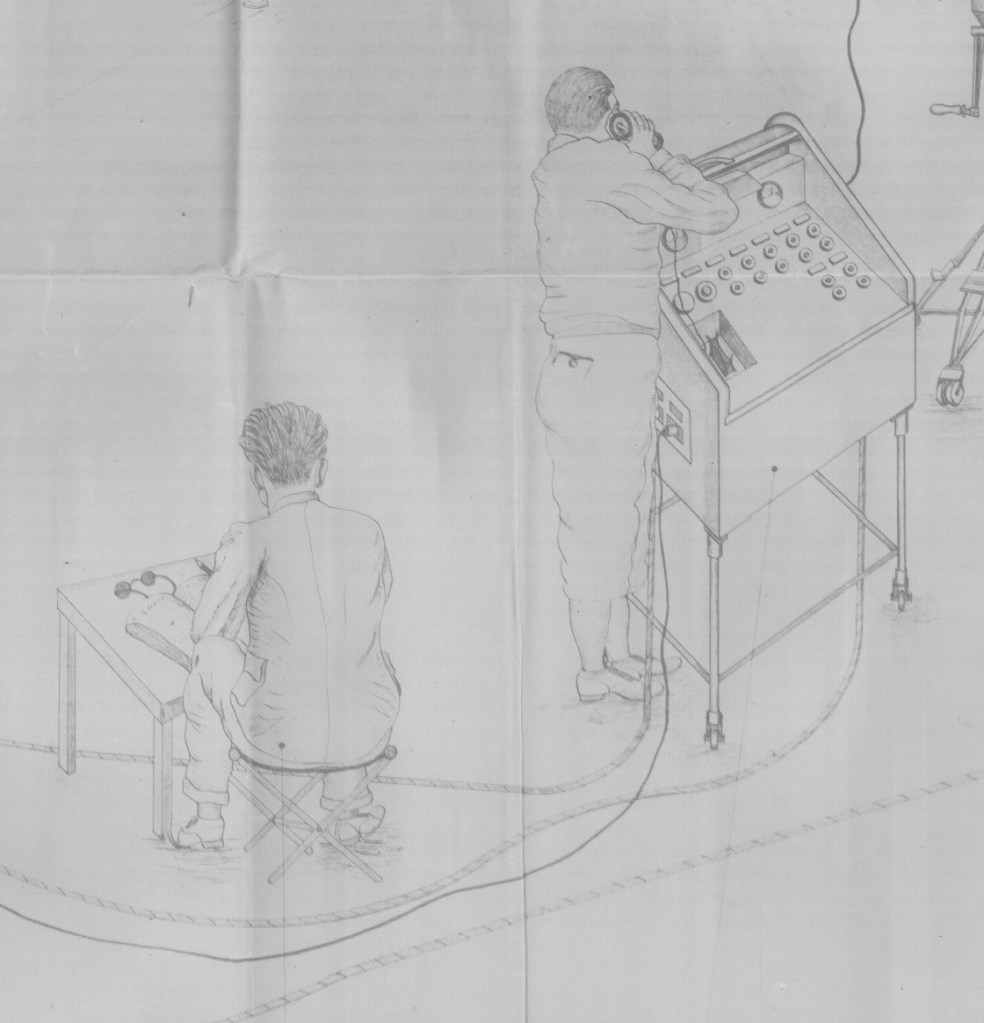

Wilhelm Scheuer’s dedicated equipment for the film studio

Archives can reveal fascinating documents. One of the most visually impressive finds for the STUDIOTEC project is in the Bundesarchiv in Berlin (File reference: BArch 117/33324). Dry descriptions offering studio technology to the studios at Babelsberg were sent in 1949 by the Wilhelm Scheuer company to promote their product range. This included rain machines, moving footways and back projection devices as well as cranes and dolleys.

The written descriptions are brought to life by the drawings that accompany them. One in particular is a large image, approximately 200cm by 120cm, in two-dimensional format, which depicts work in a studio, from the intricacies of back-projection to the engineers managing sound and light. Its beautiful draughtsmanship deserves greater recognition. Here are some of the elements that make up this image.

Materials: Balsa wood and sugar

British film studios were located in the United Kingdom, but they made use of materials brought into the country from all around the world. The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934), made at Gaumont-British’s Shepherd’s Bush studio, features a lengthy fight sequence in which no fewer than 74 chairs are smashed. That such a fracas could be committed to film without injury is testament to the skills of G-B’s props department and its ability to access balsa, the soft, lightweight wood from which the chairs were made. Kinematograph Weekly noted that the balsa used at Shepherd’s Bush was ‘specially imported from the swamps of South America.’ In all likelihood, this meant Ecuador, which between 1935 and 1941 supplied almost all of the balsa used in the United Kingdom.

A glass lampshade is shattered during the same dust-up, and elsewhere in the film numerous panes of glass are broken during an extended gunfight. The danger of deliberately shattering glass in the proximity of actors, possibly multiple times if more than one take was needed, meant that different forms of ‘breakaway’ glass were developed, often using sugar as the primary ingredient. At the time that The Man Who Knew Too Much was made, most sugar consumed in Britain originated overseas, much of it from British colonial possessions in the Caribbean.

We might talk of ‘British studios’, or ‘national film industries,’ but British filmmakers’ absolute reliance on imported goods, and personnel, means that British filmmaking was an international endeavour, one that took advantage of global networks of trade, commerce and capital, most of which were established to benefit certain countries and certain populations over others.

Settling of accounts in the studios

As soon as Paris was liberated at the end of August 1944, a purge policy was implemented in all the French studios. Initially totally informal, with plenty of room for excesses and misbehaviour, the purge was gradually organised. Local, professional and then regional committees were set up, with the aim of ousting from the profession those professionals who had actively collaborated with Germany and served the aims of the Nazi regime.

This image of an ‘exhibit’, taken from the purge file of assistant decorator Paul Boutié and kept in the archives of the Seine court, is a perfect illustration of the professional conflicts and political tensions that shook French cinema in the months following the liberation of the capital. It is a book of caricatures entitled: ‘My ally Stalin, by Winston Churchill’, which denounces the collusion between the Soviet regime and the United Kingdom. It was stamped ‘PPF’, which stands for Parti Populaire Français, a violently anti-communist and openly collaborationist political party led by Jacques Doriot. There is also a handwritten note stating that the book belongs to the assistant set designer Paul Boutié, information ‘certified by the workers of the studio de Neuilly’.

This simple book cover tells us a great deal. We can see from this document that the accusations made against this young decorator came from the manual workers who served under him at the Neuilly studios. While the painters, carpenters or electricians were hired by the studio director (Marcel Chavet), the set designer was under contract to the production company that rented the facilities, i.e. Continental Film, a German-owned company set up in Paris at the end of 1940 by the German propaganda services.

As they had no tangible evidence to support the prosecution, the workers, members of the Neuilly studios’ purge committee, were content to accuse the set designer of having pro-collaborationist views, simply because – according to them – he had a copy of a book of caricatures that had circulated among PPF members. This clearly shows the extent to which the purge was an opportunity for a kind of revenge on the part of the film workers against the production executives, even the smallest ones, who were accused – rightly or wrongly – of having taken advantage of the constraints of the Occupation to put pressure on the studio workers. In the absence of any clear evidence of collaboration, some professionals found themselves before the courts because of mere rumours, professional rivalries or personal enmities. ‘He wasn’t a good comrade’ is how many depositions read… is that enough to make him a collaborationist? Very few severe penalties were handed down by the purge tribunals and in 1945, after a few months’ suspension, Paul Boutié, like most production professionals, resumed his activities in the French studios.

Church of St Mary Magdelene, Littleton, Surrey

Sound City studio (aka Shepperton) opened in 1932 and was erected on the grounds of Littleton Park, a country estate that could trace its roots back several hundred years. Some newspapers excitedly reported that when Sound City purchased the estate, it also came into possession of something altogether more curious – an advowson. This was a piece of heritable property allowing its owner to recommend the appointment of a vicar to a specific church, in this case St Mary Magdalene in Littleton.

Alas, it turned out that these reports were incorrect. The advowson was kept in the hands of its pre-studio owners, where it remains to this day. But even so, the bizarre prospect of studio management having a say in choosing which clergyman’s sermons would be delivered from the church’s pulpit sounds like the premise for the type of film comedy film made regularly at Shepperton over the last 90 years. Although this particular avenue of research came to nought, it still made clear the long pre-histories of sites that became film studios and encouraged us to engage with them.

Snapshots of working lives – postcards to colleagues

Described as ‘the world’s first social network’ (Pyne, 2021) postcards were once a regular feature of the workplace. With a brevity to match a text message, they could convey a lot – or nothing at all. Unlike a text, however, their physical presence was a reminder of elsewhere with scenes of mountains and beaches gracing desks and walls.

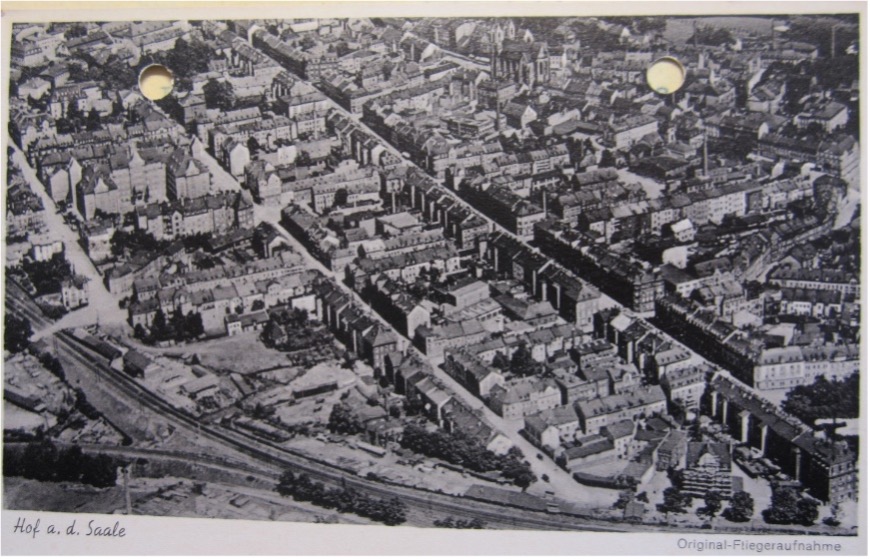

Filmstad Den Haag, one of the two Dutch studios occupied by the Germans from 1941-44.

The postcards in this scene are long lost, but occasionally the archives surrender examples. The following were sent to Ufa colleagues during the war and survived in personnel files. They were all sent by Feldpost(military post), poignant reminders that their writers were not on holiday but were keen to keep in touch with colleagues.

‘My dear colleagues. I wish you a happy and healthy Easter. Best wishes, Herbert K’. Sent on 2 April 1942.

‘Sending you best wishes from beautiful Egerland. Please give my greetings to the ladies as well! Kurt K.’ Sent on 29 March 1943.

‘From beautiful Bavaria, where it is now spring, I send you my Easter greetings! Training is progressing at a rapid pace here, and there is little free time. The fresh air is great for me, although my muscles are often sore! Kurt K.’ Sent on 20 April 1943 from Egerland.

References: BArch R 109-I/1409a; BArch R 109-I/1410a: Lydia Pyne, Postcards: The Rise and Fall of the World’s First Social Network (London: Reaktion Books, 2021).