By Richard Farmer

Dorothy Braham (The Sphere, 29 August 1931)

Born in London in 1890 and killed in a car crash in 1934, Dorothy Braham was, among other things, a Slade-educated artist, children’s book author, postcard illustrator, portraitist, animator, theatrical set designer and cinematic art director. The breadth of her interests might go some way to explaining why she is so little known; because she did not build up a significant body of work in any one of these fields (a situation no doubt exacerbated by her untimely death) it is easier for her to be overlooked than someone with a longer career in a single type of artistic endeavour, whose oeuvre is easier to identify and interrogate (Bell 2021: 6-7). It would be wrong to suggest that Braham is an entirely unknown figure in British film history. References to her work appear on the Women and Silent British Cinema website, and her name appears in publications concerning British film history, including Laurie Ede’s work on art design in British cinema (2007: 78). However, the limited amount that has been published to date about Braham’s life and work has not really given a full indication of the range of her talents and activities nor stressed her significance. Her relative obscurity might also relate to her making fairly modest films for a not especially prestigious company in a period when British films were not always held in particularly high regard – there is, for instance, no evidence that Braham won any industry award that might have prompted an exploration of her career as a whole. Braham did, though, leave traces in the historical record, and it is my intention to make use of the information I have been able to find to counter the process by which this supposedly ‘unforgettable character’ has been largely forgotten (Steele 1959: 6).

Beaconsfield studio

When Braham started at British Lion’s Beaconsfield studio she was recognised, and spoken about, as the first woman art director in Britain. Although this appears to have been an important development for both Braham and the industry, the exact date of her appointment is unclear. The earliest reference I have found to her in this role comes from December 1928, and states that by this time she had already been ‘responsible for the sets for the last three British Lion pictures,’ suggesting that she might have been in post for several months (Bioscope 1928: 113). The title of first woman art director in a British studio is more often given to Carmen Dillon, whose lengthy career in the film industry began in the 1930s and whose ‘major achievement,’ notes Laurie Ede in a history of British film design published in 2007, ‘probably lay in her breaching of the male preserve of film design’ (78). Such claims about Dillon are not new: the 21 June 1959 edition of the Sunday Times carried a piece which insisted that before her, female art directors were ‘unheard of’ (Stockwood 1959: 18). Attempts to reintroduce Braham into the history of the British film industry are just as old: Stanley H. Steele wrote to the Sunday Times the following week to sing Dorothy’s praises and set the record straight (1959: 6).

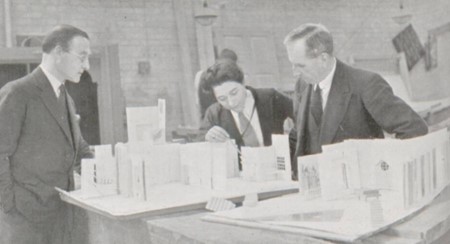

Described as an ‘art directress’ by the Daily Film Renter (31 July 1934: 4), Braham’s position as a woman in a predominantly male world made her a person of interest within British film culture. She was the subject of stories in Film Weekly (15 March 1930: 21) and the Daily Herald (2 June 1930: 8) and contributed a column to the Daily Mail (26 December 1931: 15) in which she sought to show that the techniques she employed in designing and dressing film sets could be copied by women planning and decorating their own homes. When Braham took up her position with British Lion, the Bioscope called her ‘an interesting appointment.’ This comment seems, in large part, to have been made in response to her gender. The novelty of her taking up such a senior position is noted, and she is one of only a small number of women listed in a ‘Who’s who in the British studios’ – casually titled ‘Men who make British films’ – featured elsewhere in the same edition of the paper. Most of the others were working as scenarists or in the wardrobe department. But it may also reflect the experience that she brought to the job, in that she is described as having worked in ‘all branches of decorative, theatrical and cinema art’ (Bioscope 1928: 113, 155).

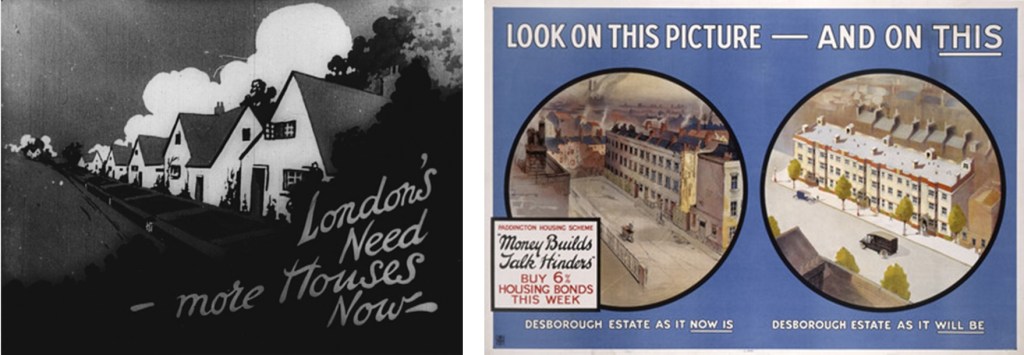

Left: LCC Housing Bonds (1920); right: housing bonds poster

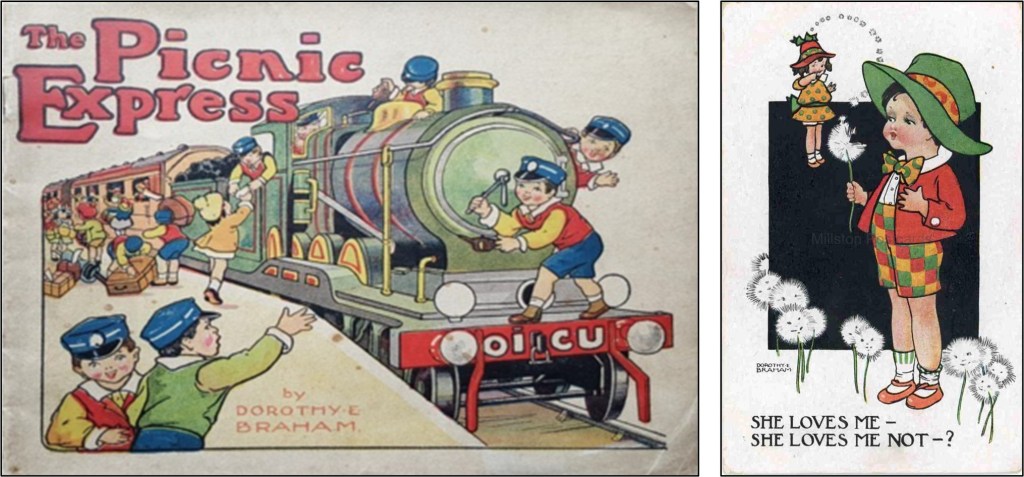

Braham moved to Beaconsfield from Gainsborough Pictures’ Islington studio, where she had initially been engaged to paint back-cloths before being taken on as an assistant art director (Bioscope 1928: 113; Chanticleer 1930: 8). It appears that she only turned to work in the theatre and cinema after the death of her father, a jeweller, left her in need of money: ‘highbrow’ portraiture wasn’t going to pay the bills (Lancashire Daily Post, 29 May 1930: 4). As is the case for most of her career, sources detailing Braham’s time at Islington are scarce. It seems likely, however, that she had already been involved with film production before starting with Gainsborough. A ‘D. E. Braham’ – Edith was Braham’s middle name – is listed on the BFI’s website as having contributed both title designs and drawings to LCC Housing Bonds (1920), a brief animated film made to encourage the public to purchase bonds from the London County Council, the revenue from which would be used to build houses. LCC Housing Bonds was well-regarded, with the Daily Herald (29 June 1920: 5) calling it an ‘ingenious rearrangement’ of the posters that Braham had designed for the same scheme and noting the involvement of Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, whose signed message concludes a film that was included in commercial cinema programmes in London and also screened across the city on mobile cinema lorries (Braham 1921: 32). The film was made so that it could be adapted to promote bond schemes in cities outside London (Best 1920: 72). It was part of a wider attempt by the government to stimulate public investment in social housing programmes. Sir Kingsley Wood, then Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Minister of Health and later Chancellor of the Exchequer, wrote a scenario on the topic of homeless veterans for production by Cecil Hepworth, although a mooted film starring Alma Taylor and James Carew remained unproduced (The Times, 16 June 1920: 17). A couple of years later, Braham provided ‘trick sub-titles’ for George F. Whybrow’s When George Was King(1922), a charity film made to raise funds for King Edward’s Hospital in London. Animation was a natural extension for Braham, given her previous work as an illustrator of both postcards and children’s books including Billy Boaster and His Motor, The Tale of Tommy Tinfoil and The Picnic Express, the last of which she also wrote.

Examples of Braham’s work as a children’s book and postcard illustrator

Profiles of Braham frequently referenced her tendency to wear what at the time were deemed ‘male’ clothes, especially trousers. Although ideas concerning ‘appropriate’ feminine dress evolved quite notably during and after the Great War, bringing about an increase in the number of women wearing trousers, Braham’s choice of clothing, and her willingness to be photographed while wearing it, was still considered something of a novelty (Bill 1993). Carmen Dillon states that when she began her first job at Fox-British’ Wembley studio in the second half of the 1930s she was told in no uncertain terms that she wasn’t allowed to wear trousers to work (De La Roche 1949: 14). Dillon’s boss was, by her own account, ‘a nasty little chap [who] didn’t like having women there at all.’ In addition to the dress code, he also told her that she wasn’t allowed to ‘order anybody about’ or ‘mix with the workmen.’ It was only during the Second World War, when male colleagues were called up, that Dillon was afforded a chance for advancement (De La Roche 1949: 14; Dillon 1993). Braham’s experience appears to have been very different; brought to Beaconsfield as an art director, she had the run of the studio and the authority and self-assurance to give directions to other members of the art department and to work in close consultation with the heads of other workshops. Braham was said by the Daily Film Renter to be ‘charming and popular’ (Daily Film Renter, 31 July 1934: 4), her ability to thrive in a predominantly male environment no doubt aided by her ‘colourful personality’ and ‘Rabelaisian turn of humour’ (Steele 1959: 6; see also Ede 2007: 78). These qualities were also shown off in a comic turn she gave at a cabaret evening organised by British Lion’s amateur dramatic society shortly before her death (Kinematograph Weekly, 31 May 1934: 26).

Braham at work (Bioscope, 5 November 1930)

Beaconsfield made the transition to sound production in 1929-30, so when Braham was engaged the films she worked on were silent productions. British Lion had purchased the studio in 1927 for the purpose of adapting some of the multitudinous works of Edgar Wallace, which were churned out at such a rate – a dozen novels in 1929 alone! – that people joked about ‘telephone callers who offered to hold the line when told that Mr Wallace was engaged, writing a serial’ (Lane 1938: 287). I am not certain of the films that Braham worked on during her first months at Beaconsfield, but titles produced in second half of 1928 include The Valley of Ghosts (1928), The Man Who Changed His Name (1928), Flying Squad (1929) and The Clue of the New Pin (1929), this last the only feature film made using the British Photophone sound-on-disc process.

Edgar Wallace on one of the sets Braham designed for The Squeaker

The need to convert the studio for sound production meant that it was closed for much of 1929, but the first film made at Beaconsfield after it reopened, The Squeaker (1930), is the only title with which, at time of writing, Braham’s name is associated on both IMDb and the BFI website. The Squeaker was an important film for British Lion, and entrusting art direction to Braham speaks to the confidence that the company had in her talents. Wallace directed the film from a script based on his 1927 novel. He proceeded at breakneck speed and Braham had to work hard to keep up (Holt-White 1930: 166-7). One report claimed, perhaps implausibly, that she was designing ‘one set a day throughout the entire production,’ which began in late February and took about a month (Lancashire Daily Post, 29 May 1930: 4). The outcome was, though, slightly underwhelming, with Kinematograph Weekly (5 June 1930: 47) declaring the sets ‘rather too restricted’ in a generally disappointing review. The next film on which we can be certain that Braham worked, Should a Doctor Tell? (1930), was rather more successful from a design point of view. Most impressively, given the film’s restricted budget, Braham worked with the studio’s chief carpenter and painter – who, in contrast to Braham, remain unnamed in contemporary press reports – to recreate the interior of the Divorce Court. This had to be done from memory as photographing and sketching the court’s interior was prohibited (Burnley News, 14 March 1931: 15). A report in The Sphere (29 August 1931: 316-7) also suggests that Braham was art director for The Calendar (1931).

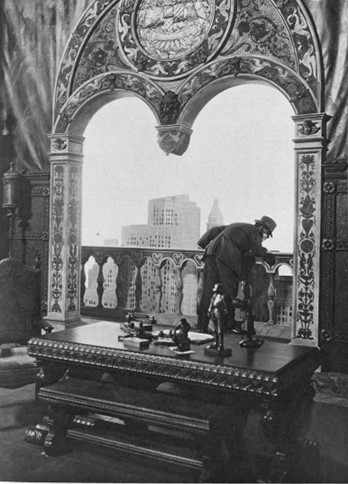

On the Spot (Sketch, 30 April 1930)

Despite his own well-known enthusiasm for tobacco, Wallace did not allow smoking ‘on any part of the premises’ while The Squeaker was being made (Lane 1938: 360). This might have proved challenging for the chain-smoking Braham, but any resentment she felt as a result of the policy was evidently not strong enough to prevent her from working with Wallace as the set designer for his new play, On the Spot, which opened in London in early April 1930. Who knows, perhaps they bonded over illicit cigarettes behind the prop store? Although supposedly written in just three days, On the Spot is said by his biographer to be ‘without doubt … Wallace’s best’ theatrical work (Farjeon 1930: 93; Lane 1938: 342). The play takes place in the apartment of Chicago gangster Tony Perelli (Charles Laughton), and the ‘sumptuously gawdy’ surroundings designed by Braham spoke to Perelli’s extreme wealth and his lack of taste, mocking his pretensions to culture – murder is done here, and corpses hidden inside expensive furniture – while simultaneously making him appear naïve and childlike, a boy playing in a wonderland of his own contriving (Woodhouse 1930: 110). The set was praised as an ‘amazing mixture of gilt and stained-glass windows’ by the Daily Mirror (3 April 1930: 2) and ‘a cross between a luxury kinema and an Italian palace’ by the People (6 April 1930: 12). In light of this latter comment, it is interesting to note that Braham had contributed to the interior design of a cinema auditorium earlier in her career, providing a ‘Japanese stage setting’ for the Kennington Theatre when it was converted to show films in 1921 (Bioscope, 3 March 1921: 8).

According to Kinematograph Weekly, Braham’s tenure as British Lion’s art director lasted three and a half years. Following the expansion of the studio and the arrival of new art director Norman Arnold, she became ‘assistant art director,’ taking charge of ‘furnishing and decorating’ at Beaconsfield (Kinematograph Weekly, 2 August 1934: 31). It seems that she was still employed by the studio in July 1934 when she embarked on a motoring holiday in north Wales, travelling with a friend with whom she shared a cottage in the Buckinghamshire village of Jordans, just a couple of miles from the British Lion studio. The friend’s name was reported variously as Mrs Irene Garne or Miss I. A Gaynor. Braham was driving near Bettws-y-Coed in Caernarvonshire when her car left the road, plunged 50 feet down a ravine, and hit a tree. Both Braham and her companion were taken to Colwyn Bay hospital (Daily Mail, 27 July 1934: 5). Braham did not survive her injuries and her body was cremated at the Golders Green crematorium on 31 July 1934.

Braham in Film Weekly (15 March 1930)

There is still, clearly, much that we don’t know about Dorothy Braham. Indeed, parts of what I have written here are somewhat conjectural, extrapolated from evidence contained in a partial historical record. This brief biographical portrait is obviously not authoritative, and I would be thrilled to learn more about Braham from anyone who can add to our knowledge of her life and work. Further research might piece together a more complete filmography, might compile a fuller list of her output as an illustrator, or might unearth more detail of her training and work as an artist. It would also allow for a better assessment of the nature and quality of her work as art director – something that I have not really sought to explore. Indeed, as we learn more about the work done by women in British film studios in the early decades of the twentieth century we might find that Braham was in fact continuing in the footsteps of earlier female art directors. Yet even though we only have fragments of a life with which to work, it has been possible to start the process of un-forgetting Braham, celebrating her as a multi-talented creative force and vibrant personality.

References

Melanie Bell (2021). Movie Workers: The Women Who Made British Cinema (Urbana: University of Illinois Press).

Jos. Best (1920). Letter in Kinematograph Weekly, 15 July, p. 72.

Katina Bill (1993). ‘Attitudes Towards Women’s Trousers: Britain in the 1930s’, Journal of Design History, 6:1.

Bioscope British Film Number 1928 (1928), 12 December.

D. E. Braham (1921). Letter in Bioscope, 21 July, p. 32.

Chanticleer (1930). ‘Woman art director’, Daily Herald, 2 June, p. 8.

Catherine De La Roche (1949). ‘Carmen Dillon’, Picturegoer, 16 July, p. 14.

Carmen Dillon (1993). Interview with Sidney Cole, BECTU History Project, 23 June. https://historyproject.org.uk/sites/default/files/Carmen%20Dillon_0.pdf

Laurie Ede (2007). ‘Art in context: British film design of the 1940s’, in James Chaman, Mark Glancy and Sue Harper (eds), New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 73-88.

Herbert Farjeon (1930). ‘The London stage’, Graphic, 12 April, p. 93.

W. Holt-White (1930). ‘Filming The Squeaker’, The Sphere, 26 April, p. 166-7.

Margaret Lane (1938). Edgar Wallace: the biography of a phenomenon (London: William Heinemann).

Stanley H. Steele (1959). Letter in Sunday Times, 28 June, p. 6.

Jane Stockwood (1959). ‘Feminine art in films’, Sunday Times, 21 June, p. 18.

Vernon Woodhouse (1930). ‘Crime in Chicago’, Bystander, 16 April, p. 110.